MIT Researchers Develop Ionic Neuromorphic Chips to Cut AI Energy Use by Up to 1,000×

Image Credit: Ayush Kumar | Splash

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are advancing neuromorphic computing designs that draw directly from human brain mechanics to slash the power demands of artificial intelligence systems, addressing a core challenge in the field's rapid expansion.

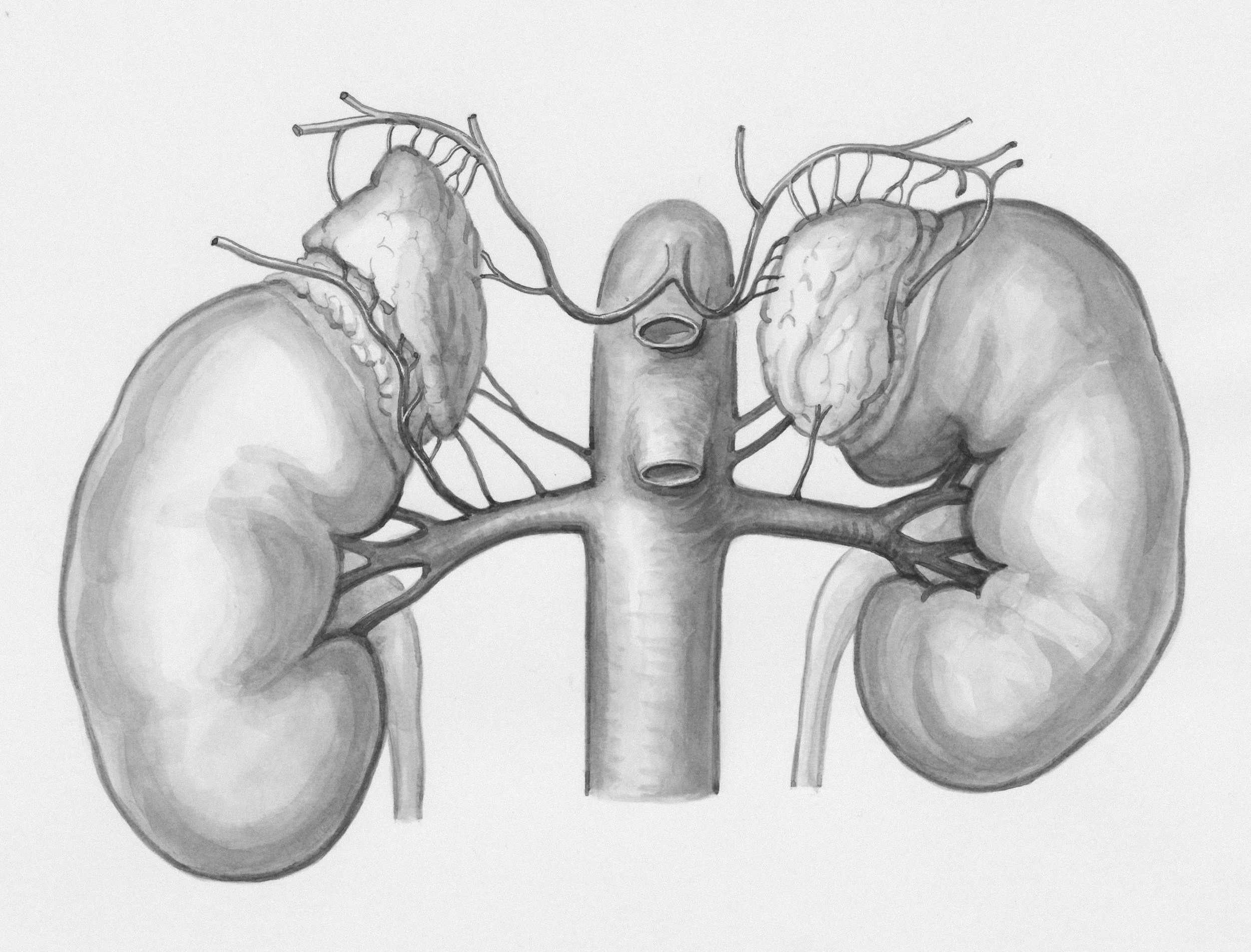

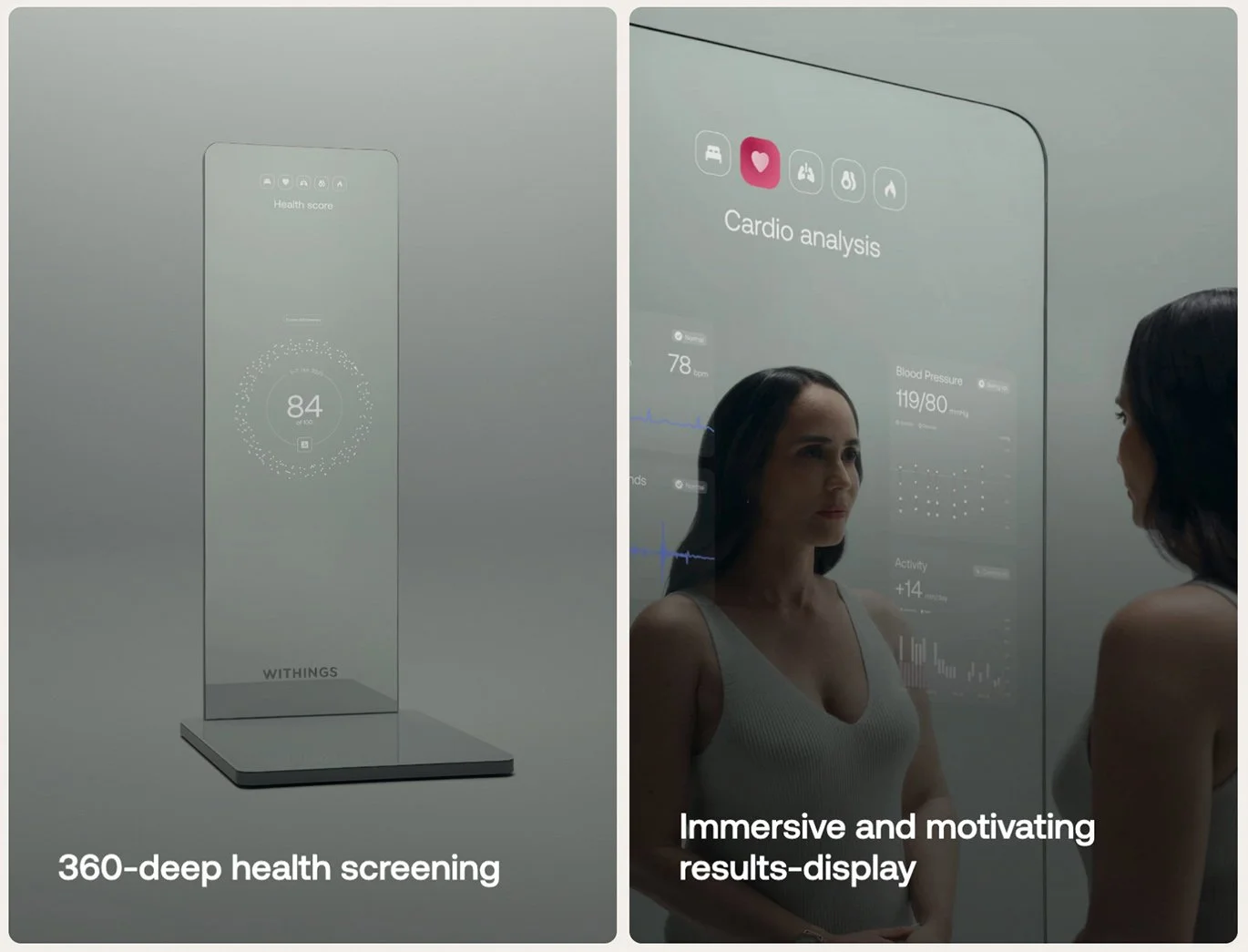

In a project blending materials science and neuroscience, PhD candidate Miranda Schwacke has engineered prototype electrochemical devices that mimic synaptic connections in the brain, allowing data processing and storage to occur in one spot rather than shuttling between separate units as in traditional chips. This approach could enable AI applications in power-constrained environments, such as wearable health monitors or remote sensors, where current systems drain batteries quickly.

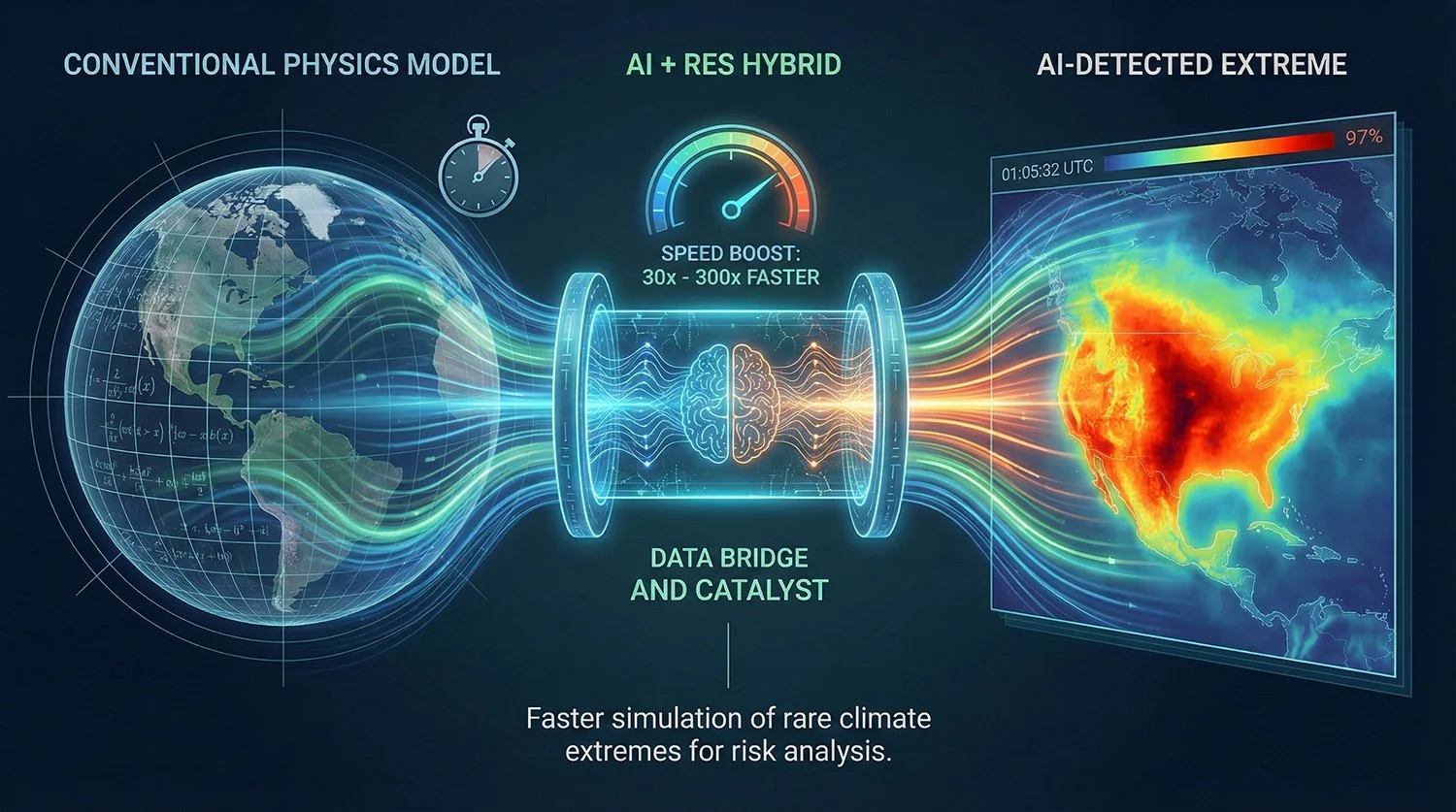

Schwacke's work, overseen by Professor Bilge Yildiz in MIT's Department of Materials Science and Engineering, targets the inefficiencies plaguing modern AI. Training large language models or neural networks today guzzles electricity - often equivalent to the output of small power plants - because digital processors handle computation and memory as distinct tasks, creating constant data transfers that waste energy. By contrast, the human brain manages complex learning with just 20 watts, roughly a fifth of an incandescent globe's draw, through electrochemical signals at synapses that adjust strength on the fly.

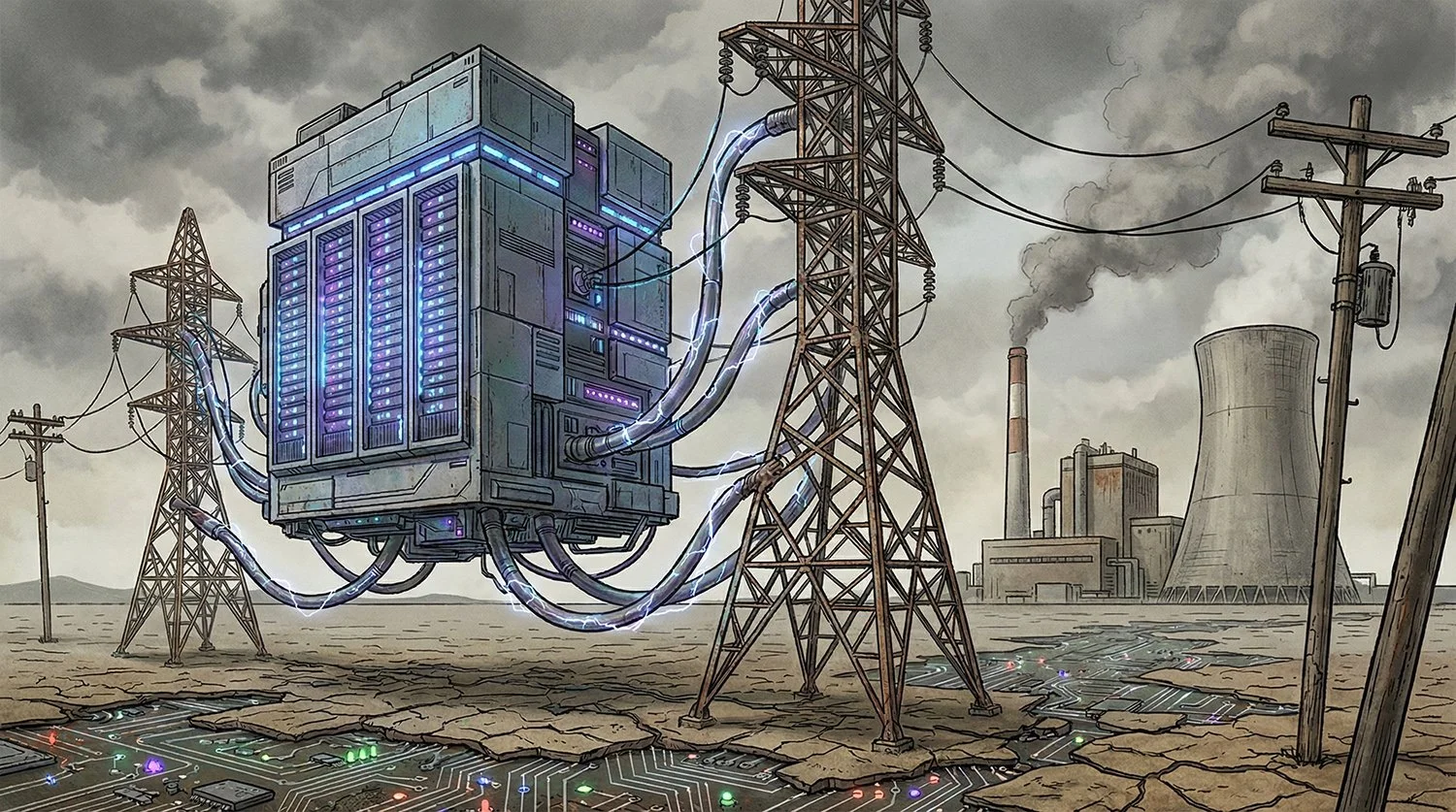

Roots in Rising AI Power Crunch

The push for such hardware stems from AI's explosive growth since the mid-2010s, when deep learning breakthroughs like convolutional networks for image recognition demanded ever-larger datasets and models. Global data centre energy use, much of it AI-driven, sat at 240-340 terawatt-hours in 2022 according to the International Energy Agency, with base case projections reaching around 945 TWh by 2030.

At MIT, this intersects with broader sustainability goals. Yildiz's lab, which probes ion movements in energy tech like batteries, pivoted to computing in response to these trends. Schwacke joined in autumn 2020 after a virtual chat with Yildiz, drawn by the chance to apply her Caltech background in electrochemical systems to AI's environmental footprint. Her early experiments built on solid-state ionics from fuel cell research, adapting principles where charged particles shuffle through materials to enable reactions.

This aligns with a decade-long neuromorphic push across academia. Pioneers like Intel's Loihi chip in 2017 demonstrated spike-based processing akin to neurons firing, with reported gains up to 1,000 times in energy efficiency for select edge AI tasks compared to traditional processors, though academic studies often show lower but still substantial improvements depending on the workload. Yet scaling remains tricky, as silicon-based mimics struggle with the brain's fluid, analog nature. MIT's ionic focus offers a fresh angle, using wet-chemistry echoes in dry hardware for finer control.

Building Blocks: From Ions to Synapse Mimics

Schwacke's core innovation involves tungsten oxide thin films as conductive channels, tuned by inserting magnesium ions to vary electrical resistance - a stand-in for how brain synapses bolster or dampen signals during learning. Unlike volatile hydrogen ions, which destabilise devices, magnesium provides stability while allowing precise modulation, tested via probe stations that measure resistance shifts under voltage.

These "ionic synapses" operate electrochemically: apply a pulse, and ions migrate, altering conductivity without full data reloads. Early prototypes, fabricated in MIT's cleanrooms, clock in at micron scales, with potential to fit billions onto a chip like today's billion-transistor GPUs but with local updates inspired by biological rules.

Collaboration spans disciplines. Yildiz teams with labs across neuroscience at MIT, such as those studying songbird vocal learning - where dopamine rewards tweak synapses locally, bypassing global recalculations like AI's backpropagation algorithm. Electrical engineer Jesus del Alamo and mechanician Ju Li contribute on integration with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor tech, the backbone of current chips. Prototypes so far handle basic signal tuning, with MATLAB scripts analysing ion flows for reliability.

Challenges persist: ensuring devices switch fast enough for real-time AI, like voice recognition, while sipping picojoules per operation. Schwacke's 2023 and 2024 MathWorks fellowships funded these tweaks, including noise reduction in resistance readings.

Real-World Ripples for AI Deployment

For AI practitioners, the payoff lies in "always-on" intelligence without grid-scale power. Imagine smartwatches running full neural nets for gesture detection on a coin-cell battery, or IoT networks in farms processing crop data onsite, curbing the ICT sector's estimated 1.5-4 percent of global carbon emissions.

Yildiz envisions million-fold efficiency gains over silicon baselines, per synaptic event energies of 1-100 femtojoules - dwarfing the 10-100 picojoules in today's neuromorphic prototypes. This could democratise AI beyond cloud giants, aiding climate models or medical diagnostics in off-grid areas.

Broader industry echoes the urgency. Still, commercial hurdles loom: fabs must adapt for exotic materials, and software needs rewriting for spike-timing codes over matrix maths.

Horizons: Scaling Brain Tech Amid AI Boom

Looking ahead, MIT's efforts signal a shift from brute-force scaling to bio-mimicry as Moore's Law fades. By 2030, analysts forecast neuromorphic markets at around USD 8.6 billion, driven by edge devices where latency and power trump raw flops, according to Allied Market Research.

Schwacke's trajectory - from solar cell theses in high school to ionic chips - underscores the interdisciplinary grind. As she notes, bridging electrochemistry and semiconductors means sifting "messy data" for patterns, much like AI trains on noise. If prototypes mature, they could interface directly with neural tissue, blurring machine and mind for prosthetics.

Yet sceptics caution: brain complexity defies full replication, and hybrid digital-analog chips may prevail over pure overhauls. For now, this MIT strand adds credible momentum to sustainable AI, one ion at a time.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.