UK Elections 2026: Regulators Target Political Deepfakes With New Unit

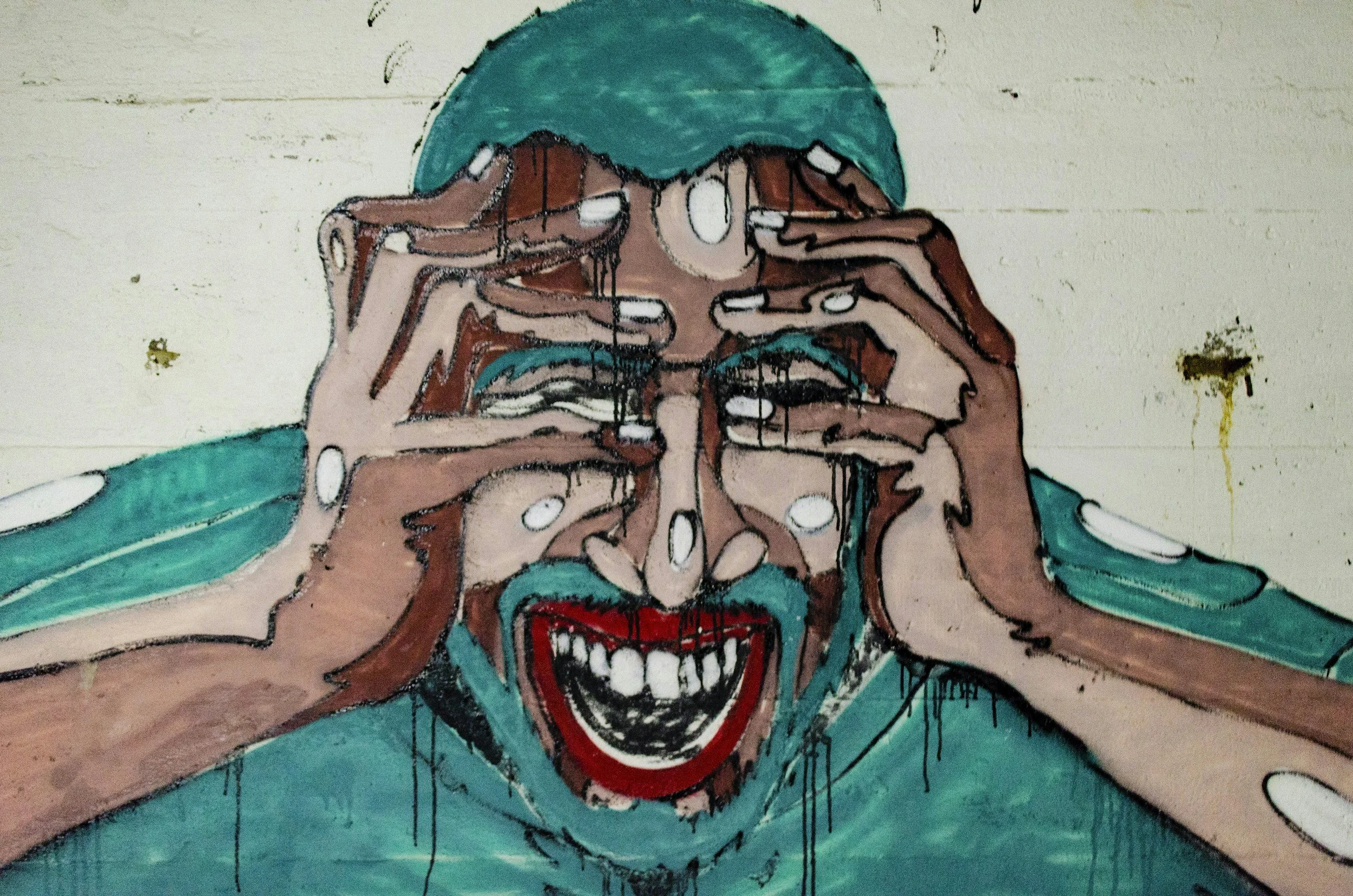

Image Credit: Toni Pomar | Splash

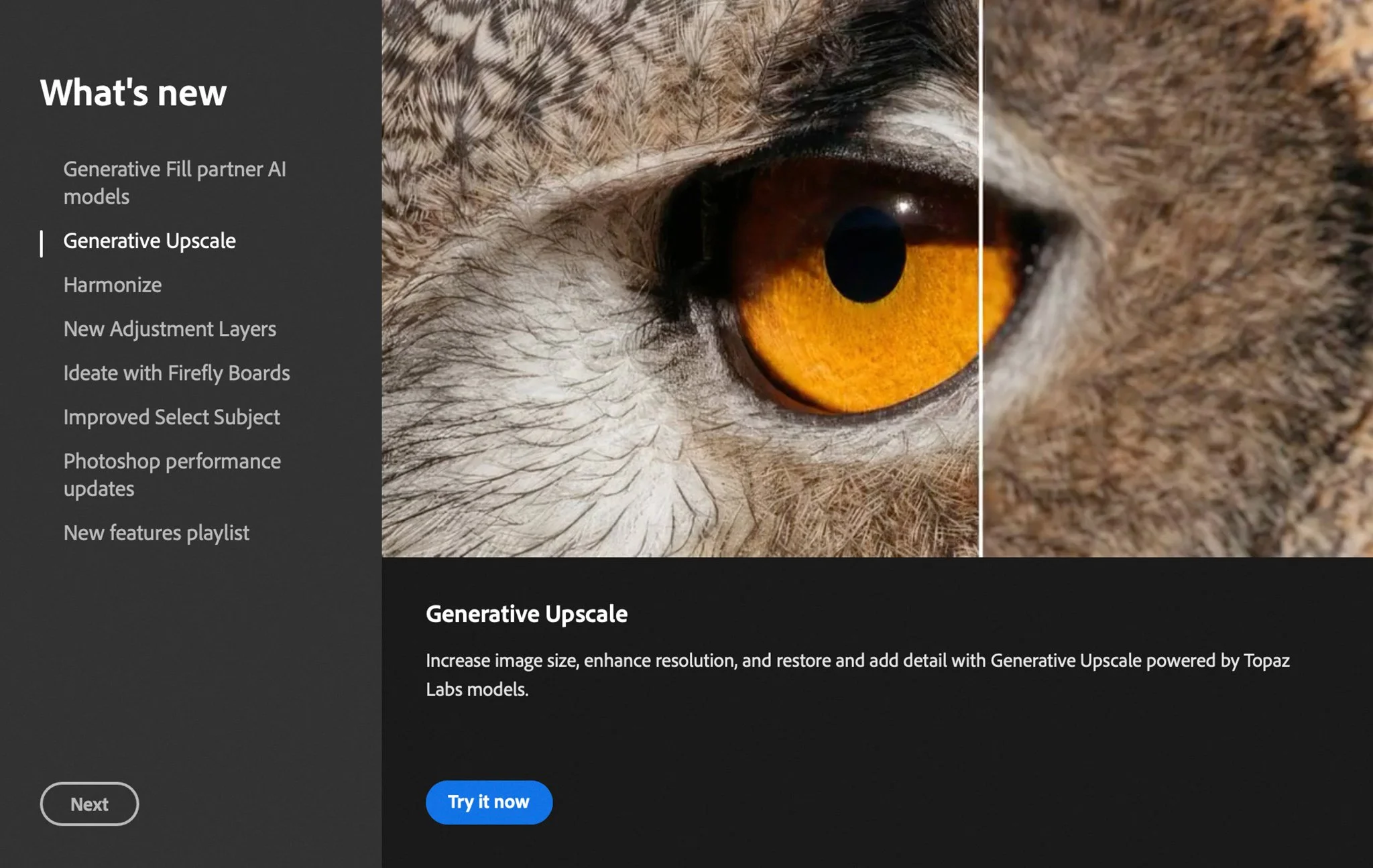

A new warning about political deepfakes is landing just as the United Kingdom enters the formal regulated period for the 7 May 2026 elections in England, Scotland and Wales. The Observer reported that AI generated impersonations are increasingly targeting politicians, and that election officials are preparing a more proactive response in the lead up to polling day.

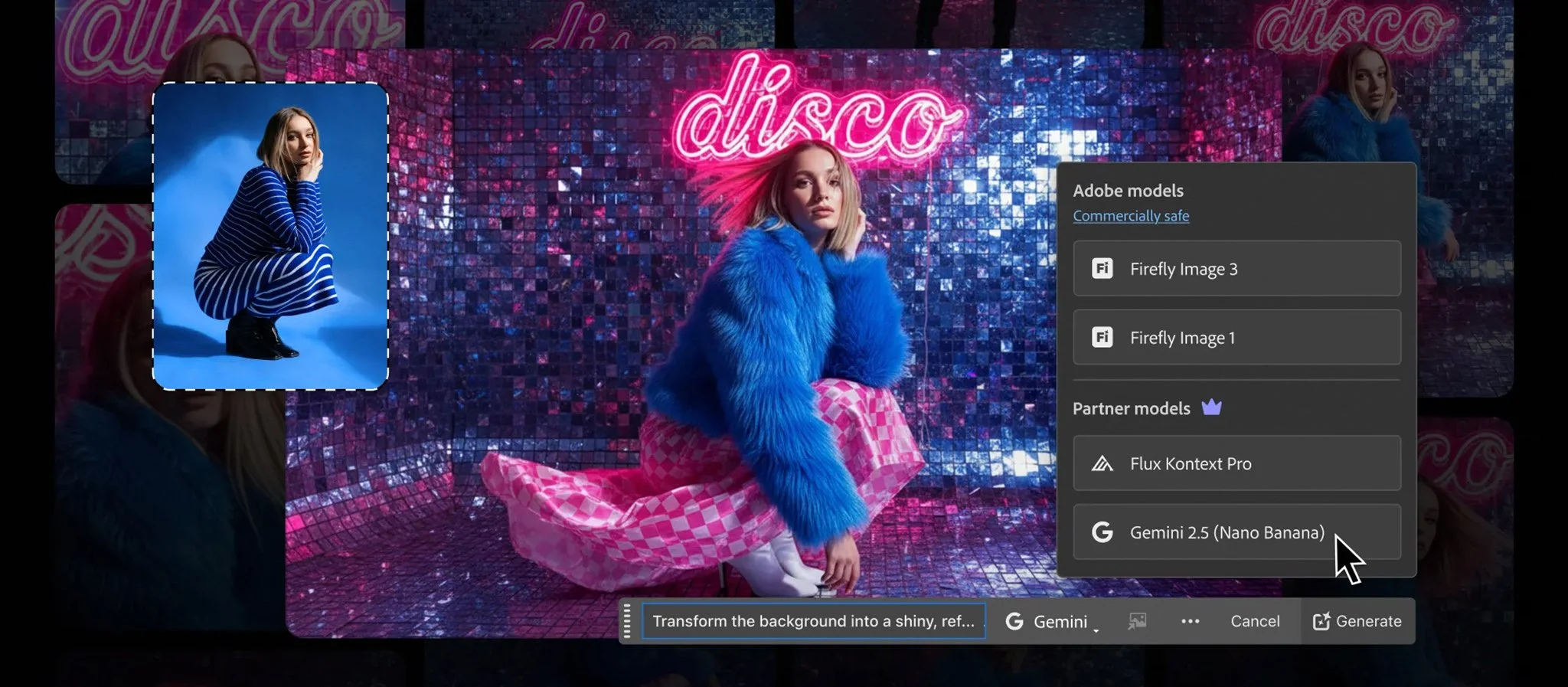

The issue is not simply that synthetic media exists. It is that modern generative AI can produce short clips that look and sound convincing enough to travel quickly on social platforms, often before context and corrections catch up. Election administrators, platforms and lawmakers are now being pushed to answer a difficult question: how do you preserve open political debate while reducing the damage from content designed to mislead voters about what candidates actually said or did.

George Freeman was Defecting to Reform UK?

The Observer’s report is built around the experience of Conservative MP George Freeman, who said an AI generated video made it appear he was defecting to Reform UK. He reported it to police and also raised concerns with Meta about takedown decisions.

The timing matters because the UK Electoral Commission lists 7 January 2026 as the start of the regulated period for campaign spending rules ahead of the May polls. That does not automatically mean a new deepfake law begins today, but it does mean the campaign environment is formally shifting into election mode, where misleading content can have outsized impact, especially at local and devolved election level.

More Than DeepFake Videos

Recent UK examples show that the “deepfake” label covers multiple patterns, not just high end video.

Impersonation clips aimed at political credibility: Freeman’s case is a classic impersonation scenario: realistic face and voice, plausible setting, and a message designed to trigger strong reactions quickly.

Manipulated audio and “cheap fakes” that still spread: During the UK’s 2024 general election campaign, fact checkers documented clips where audio was altered to make politicians appear to say something inflammatory. One widely shared example involved Wes Streeting, where a clip was circulated with doctored audio.

Synthetic content that can inflame tensions offline: In 2024, Sadiq Khan described an AI generated audio clip imitating him that he said risked “serious disorder”. Whatever the production quality, the key risk is behavioural: content that stokes anger can move from online outrage to real world confrontation.

Sexualised deepfakes targeting women in politics: Separate reporting has documented AI generated fake pornography targeting British female politicians, naming multiple high profile figures. This matters for elections because it can deter participation and campaigning, especially for women candidates, and it can be deployed as a form of harassment rather than persuasion.

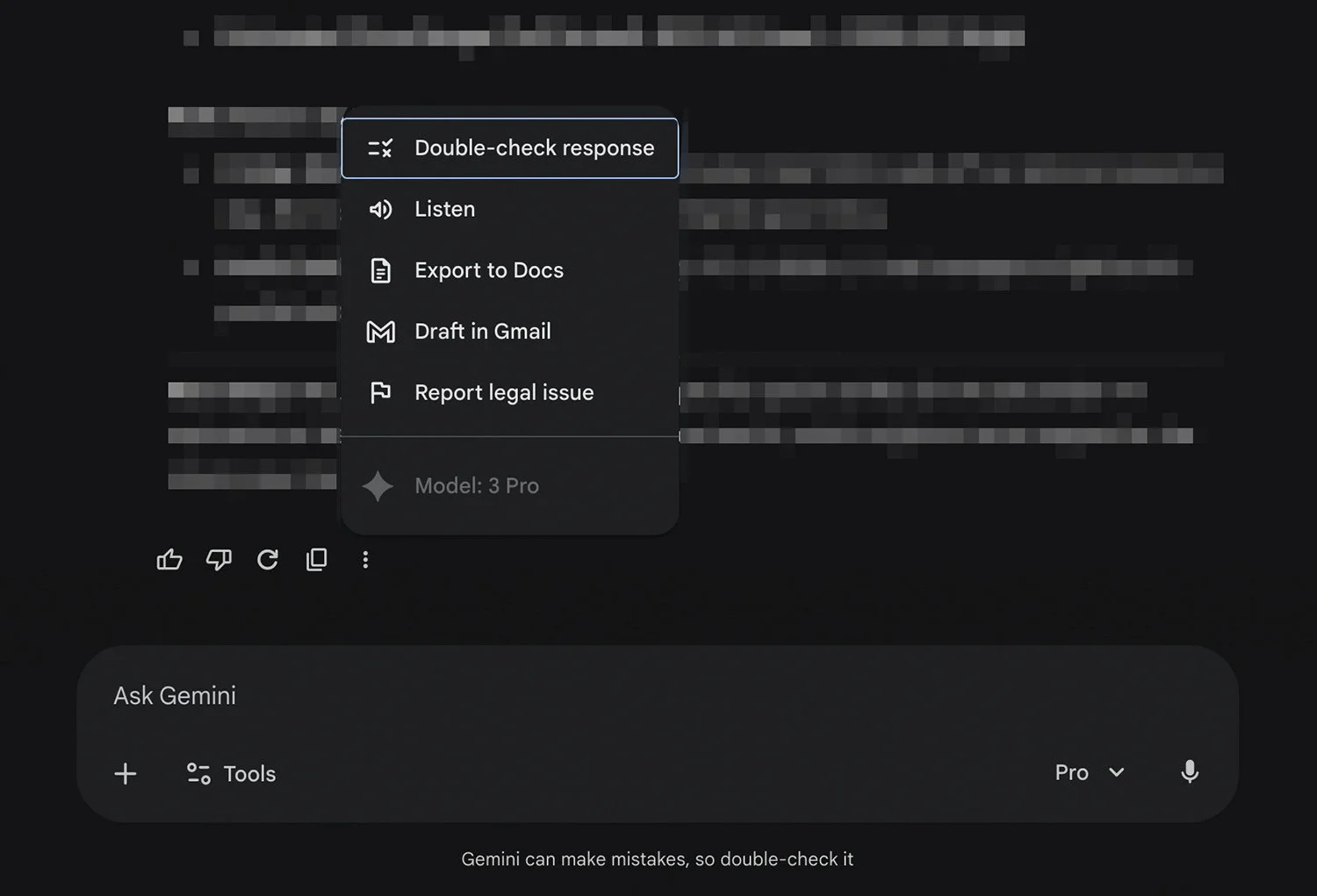

The UK Electoral Commission is Taking Action

The most operational detail in the Observer report is that the UK Electoral Commission is setting up a new unit ahead of the May 2026 elections to identify and seek takedowns of political deepfakes, with monitoring across major platforms and an ability to handle content in Welsh as well as English. The Observer also reported the work is being developed in collaboration with the Home Office, and that candidates will be able to contact the Commission for support if a deepfake circulates.

The report frames this as an attempt to reduce the time between a deepfake appearing and election stakeholders responding, which is often where the damage happens. Even if a clip is later debunked, early exposure can still shift impressions, especially among people who see the content once and never see the correction.

There Are Still Gaps

The UK’s current approach is a patchwork: some content may be caught by existing law depending on what it contains, but political deepfakes as a category can still slip through.

On the platform regulation side, the Online Safety Act includes duties around “content of democratic importance”, designed to protect political debate while platforms meet broader safety obligations.

But election integrity debates keep returning to a practical gap: a political deepfake can be harmful without being clearly illegal in a way that triggers fast removal or clear enforcement. The Observer story reflects that tension by reporting on takedown decisions and the push for rules that are more explicit about deceptive synthetic political media.

Independent research commissioned or cited by UK regulators has also highlighted how deepfakes can sit alongside other manipulation techniques during election periods, and why response speed matters when content spreads through recommender systems.

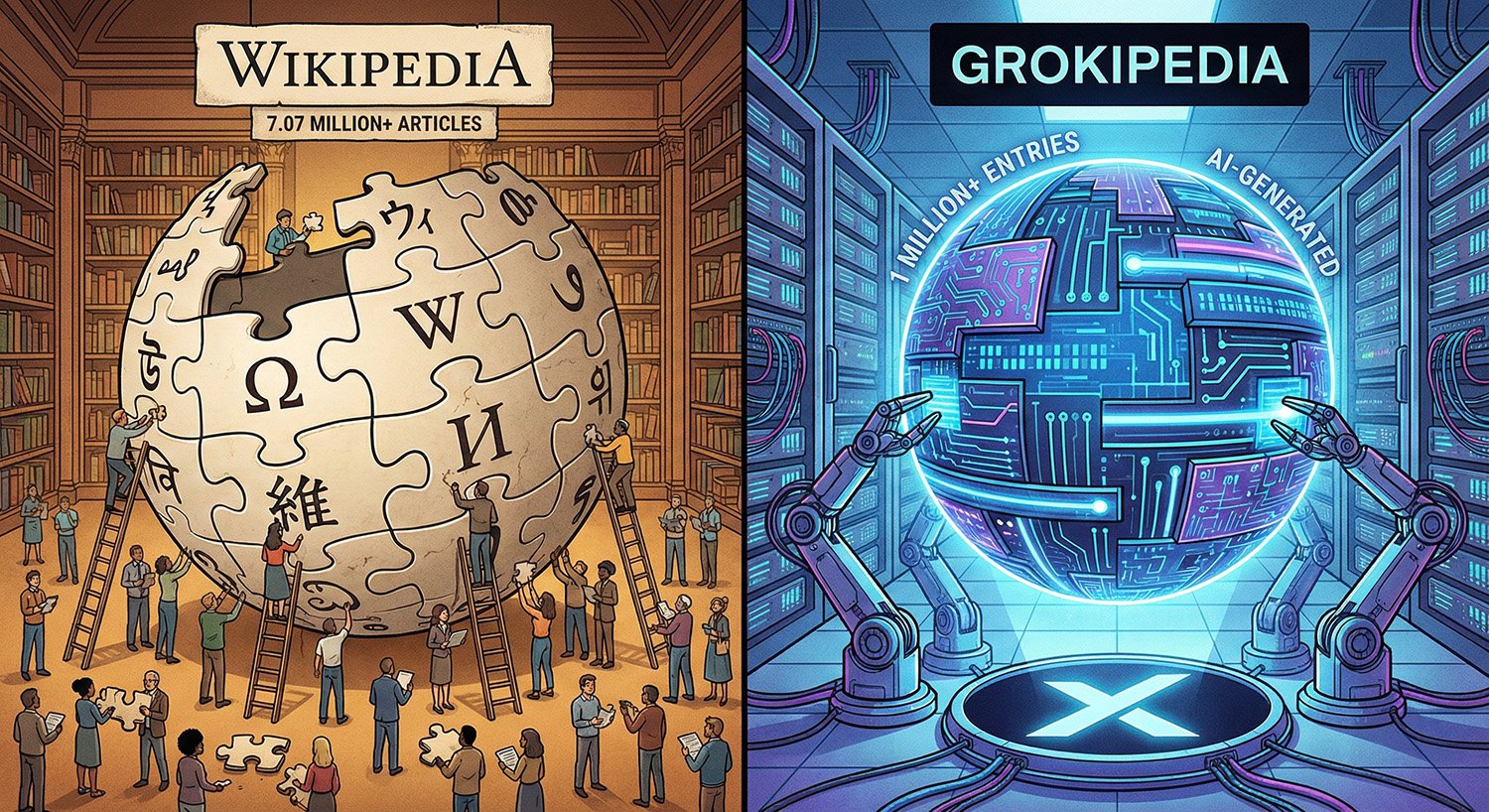

Compared with the Australian Rule

In Australia, the policy direction has leaned heavily on disclosure and voter education, plus some state level tightening.

The Australian Electoral Commission says it does not regulate the truth of political claims, but notes that AI generated content, including deepfakes, may be subject to authorisation requirements depending on how it is communicated. It also points voters to practical checks because AI can be used in persuasive ways, even when content is not outright fabricated.

At state level, South Australia has moved further on political deepfakes in election advertising. SA’s government says reforms for the March 2026 state election include rules aimed at deepfake political ads, alongside restrictions on robocalls and robopolls and strengthened authorisation requirements.

The contrast is useful: the UK debate is currently being driven by operational detection and takedown readiness before May 2026, while Australia’s federal messaging has focused on voter resilience and transparency, with some states pursuing more explicit guardrails on synthetic political advertising.

What to Watch?

Three signals will matter most in early 2026.

First is speed: whether election bodies and platforms can shorten the time between upload, verification and action. The Observer report suggests the UK Electoral Commission is designing exactly for that problem.

Second is labelling and provenance: whether disclosure becomes normal for legitimate campaign use of AI, and whether platforms enforce consistent rules for manipulated media in political contexts.

Third is candidate safety and participation: the growing intersection between election integrity and abuse, particularly sexualised synthetic content aimed at women in public life. That trend is already documented in UK reporting and is increasingly discussed as a democratic risk, not only a personal harm.

License This Article

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.