AI in Democracy: 150,000 Votes in Tokyo and 55% Legal Adoption in Brazil

AI-generated Image (Credit: Jacky Lee)

Experts in cybersecurity and data science are highlighting how artificial intelligence is already changing the nuts and bolts of democratic life, from courtrooms to election campaigns, while warning that poorly designed tools can mislead voters and entrench bias.

In a recent opinion piece for The Guardian, data scientist Nathan E. Sanders of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center and security technologist Bruce Schneier, a lecturer at Harvard Kennedy School and chief of security architecture at Inrupt, described four real-world deployments of AI that are supporting democratic processes in Brazil, Japan, Germany and the United States. Their article draws on their new book, Rewiring Democracy: How AI Will Transform Our Politics, Government, and Citizenship, published by MIT Press on 21 October 2025. The pair argue that AI, if governed as public infrastructure rather than left solely to private platforms, can ease long-standing bottlenecks in courts and political institutions without replacing human judgement.

Judicial Efficiency Gains in Brazil

Brazil provides one of the clearest examples of AI being used to cope with an overburdened justice system. The country has long been described as highly litigious: national statistics record tens of millions of pending lawsuits, and analyses cited by Sanders and Schneier note that Brazil spends roughly 1.6% of GDP on running the judiciary, plus a further 2.5–3% of GDP on court-ordered payments by governments. Together, these figures make the cost of litigation a significant macroeconomic issue.

Since the late 2010s, Brazil’s courts have rolled out AI systems to help manage that load. The Supreme Federal Court (STF) worked with academic partners to build VICTOR, a system that automatically classifies incoming appeals, routes them to the appropriate justice and checks whether they raise issues already settled as binding precedents. Similar tools are used across the judiciary to:

distribute cases among judges

assist with legal research

transcribe hearings

flag duplicate filings

draft initial orders or dispatches

cluster similar cases to be handled together

These systems sit on top of a national AI infrastructure managed by Brazil’s National Council of Justice (CNJ), which has also created a shared platform for training and auditing models.

Results have been measurable, even if not solely attributable to AI. The STF reports that its backlog is now at its lowest level in more than three decades, despite an increase in the number of new filings. Case-study research on VICTOR describes tests in which the system classified hundreds of appeals in under a second, compared with manual review times measured in tens of minutes per case. For judges, this means more time spent on substantive deliberation and less on sorting through repetitive paperwork.

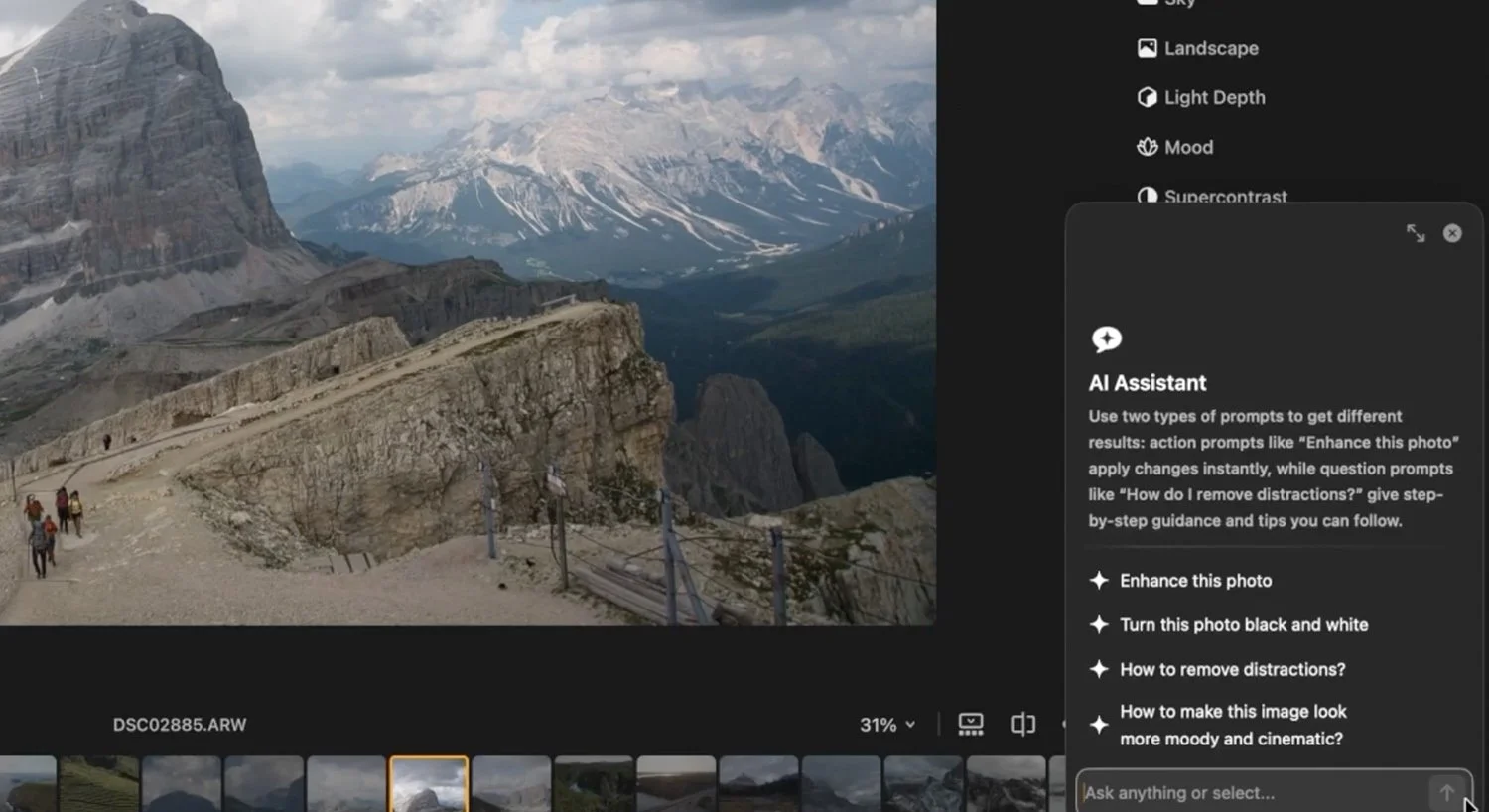

At the same time, AI is spreading rapidly among lawyers themselves. A national survey conducted by OAB São Paulo, Trybe, Jusbrasil and ITS Rio in 2025 found that just over half of Brazilian legal professionals already use generative AI at least once a week in their work, mainly for summarising documents, drafting filings and researching case law. For many law offices, these tools have quickly become embedded in everyday practice.

Regulators have tried to get ahead of the trend. CNJ Resolution 332/2020 sets ethical and governance rules for AI in the judiciary, emphasising transparency, mechanisms to monitor bias and a ban on predictive-sentencing tools in criminal cases. Later resolutions, including 455/2022 and its 2024 update, focus on digital communications and electronic service of process, reflecting a broader shift to data-driven courts rather than AI alone.

Researchers and judges caution that the same tools which ease administrative burdens can also encourage more litigation by lowering the cost of drafting. Sanders and Schneier note that AI in Brazil functions both as an engine of efficiency and as infrastructure for citizen participation: easier access to the courts can strengthen accountability, but only if systems are rigorously audited to ensure they do not amplify existing inequities in legal access.

Voter Engagement Boost in Tokyo

If Brazil’s courts illustrate AI behind the scenes, Tokyo offers a public-facing experiment in AI-mediated campaigning.

During the July 2024 Tokyo gubernatorial election, independent candidate Takahiro Anno, an AI engineer and writer, ran what he described as a low-budget campaign with little conventional media backing. Working with the AI Objectives Institute, he built an AI avatar trained on his policy platform and deployed it in a 17-day continuous YouTube livestream. According to analyses cited by Sanders and Schneier and independent academic work on AI and democracy, the avatar answered around 8,600 questions from voters, day and night.

The system was built on a participatory platform known as “Talk to the City”, originally developed for civic engagement projects. It was configured to respond consistently with Anno’s stated positions while organising incoming questions around recurring themes such as childcare, public transport and fiscal policy. Voters could ask about specific concerns and receive immediate answers, with the conversation evolving as more people participated.

In an extremely crowded field of 56 candidates, Anno finished fifth, receiving roughly 150,000 votes. Commentators noted that this was an unusually strong performance for a candidate in his early thirties without a major party behind him. While the avatar did not change the election outcome, it gave many Tokyo residents a level of direct access to a candidate that traditional rallies or televised debates struggle to match, particularly for younger voters who primarily engage online.

Anno has since founded a political group, Team Mirai, which campaigns on digital democracy and social policy. In the July 2025 House of Councillors election, Team Mirai won a proportional representation seat with around 2.6% of the national vote, and Anno took office as a member of the upper house on 1 August 2025. His use of AI-mediated engagement has therefore moved from an experimental campaign tool into an ongoing element of his work as a legislator.

The Tokyo case stands out for its overt labelling of AI. The avatar was clearly presented as a tool speaking on Anno’s behalf, not as a deepfake or a covert proxy, and his team emphasised that final decisions remained with human campaign staff. For scholars of political communication, it offers an early example of how AI might expand participation in large cities where most residents will never meet a candidate in person.

German Research Flags Reliability Risks

While Brazil and Japan highlight the upside of carefully designed systems, a German study has become a touchstone for the risks of handing public information tasks to unvetted AI tools.

Germany’s official Wahl-O-Mat has, since 2002, provided voters with a structured questionnaire that matches their answers to parties’ stated positions. It is run by the Federal Agency for Civic Education and developed with input from panels of young people and political scientists to keep questions balanced and transparent. Ahead of federal and European elections, millions of voters use it as a reference point.

In the run-up to the 2025 federal elections, AI-based voting advice applications (VAAs) emerged as unofficial competitors. Tools such as Wahlweise and AI chatbots that claimed to summarise party positions promised more conversational guidance, sometimes powered by large language models. These systems were not operated by public agencies and typically disclosed little about their underlying data or prompt design.

A research team led by Ina Dormuth at the University Alliance Ruhr put some of these systems to the test. In a paper first released on arXiv in February 2025 and later presented at a conference on explainable AI, they compared AI outputs to official party responses on 38 Wahl-O-Mat statements.

Their findings were stark:

Commercial large language models tended to show strong alignment with left-leaning parties, but much weaker alignment with centre-right and right-wing parties.

Some AI-based VAAs deviated from parties’ official positions in a quarter to more than half of all cases, depending on the system tested.

Under simple changes in prompts, one tool produced serious hallucinations, including fabricated claims that parties had ties to extremist organisations.

The researchers emphasised that Wahl-O-Mat’s content goes through a transparent, multi-stage vetting process, whereas the AI systems they evaluated did not disclose their training data, internal prompts or safeguards. Their conclusion was that tools which appear “neutral” on the surface can encode substantial ideological bias and factual error if they are built on general-purpose models not tuned or audited for local political contexts.

German security agencies have separately warned that foreign actors could exploit generative AI to spread misleading or synthetic political content. The domestic intelligence service and the federal cyber-security authority have both listed AI-generated disinformation and deepfakes among the risks to democratic stability, even though confirmed large-scale incidents remain relatively limited so far.

Across Europe more broadly, regulatory responses are still catching up. The EU AI Act, politically agreed in 2024, will introduce obligations for “high-risk” AI systems and transparency rules for certain generative uses, but most of its provisions will not be fully in force for several years. In the meantime, election-related transparency has relied primarily on the Digital Services Act and voluntary codes of practice for online platforms rather than AI-specific law.

Broader Implications and the Road Ahead

Taken together, these case studies show AI acting as both infrastructure and experiment in democratic systems.

In Brazil, AI is deeply embedded in court administration, where it helps sort and route millions of cases under written ethical rules and oversight by the CNJ. The same technologies are spreading across the legal profession, changing how lawyers prepare cases and interact with the state.

In Tokyo, AI has been used to expand direct dialogue between a candidate and hundreds of thousands of potential voters, with clear labelling and human control, and has now followed that candidate into institutional politics through Team Mirai’s presence in the upper house.

In Germany, experiments with AI-based voting advice show how quickly such tools can misrepresent party positions or inject invented facts if they are not designed and audited with the same care as established public services like Wahl-O-Mat.

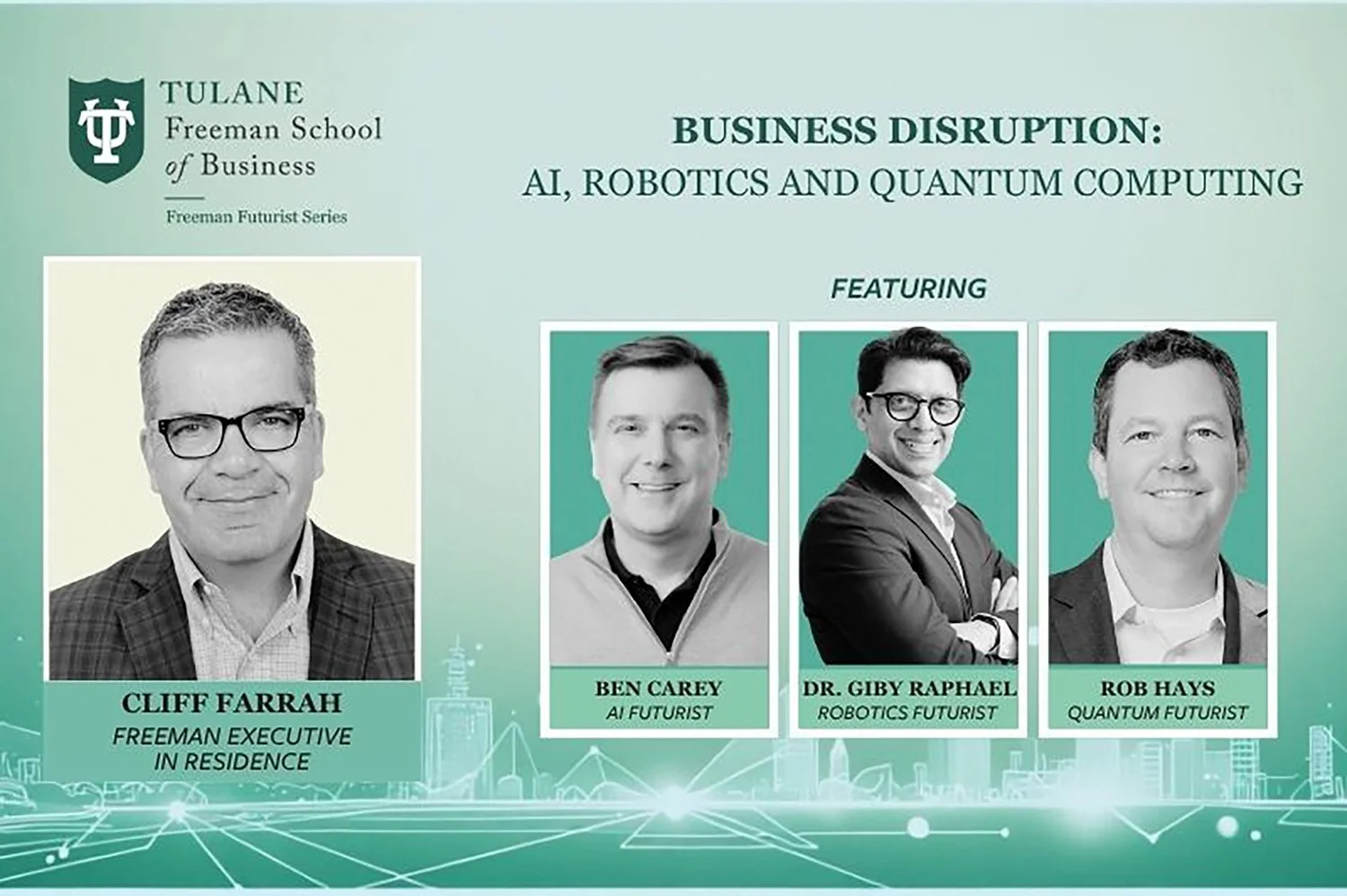

Sanders and Schneier argue in Rewiring Democracy that the key question is not whether AI will enter politics and government — it already has — but who controls it and under what rules. Their book and related essays call for “public AI” projects: systems commissioned, governed and scrutinised by democratic institutions, with open procedures and participatory design, rather than purely proprietary black boxes.

International bodies are beginning to move in this direction. UNESCO, for example, has run a series of “AI and the Rule of Law” conferences and training programmes for judges and regulators since 2023, focusing on transparency, accountability and fundamental rights.

As a busy election calendar unfolds in 2025 and beyond, the Brazilian, Japanese and German experiences illustrate possible futures. AI can help courts clear backlogs and give voters new ways to scrutinise candidates. It can also, if poorly governed, mislead citizens or reinforce structural biases. Whether it ultimately strengthens or weakens democracy, Sanders and Schneier suggest, depends less on the models themselves than on the institutional choices societies make about how — and for whom — those models are built.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.