UK Fast-Tracks AI Drones & Defence Tech by Cutting Regulatory Red Tape

Image Credit: Mark Stuckey | Splash

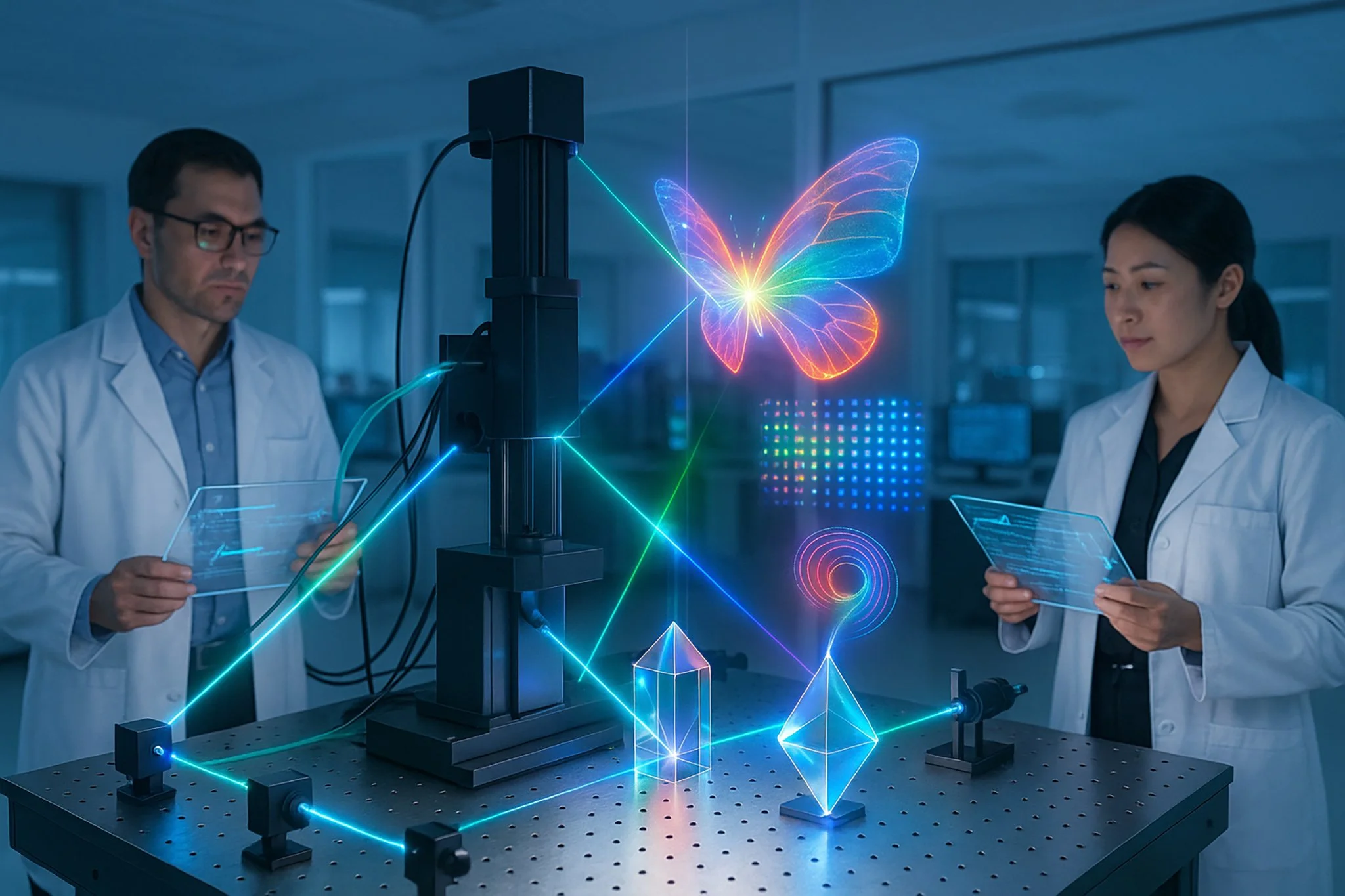

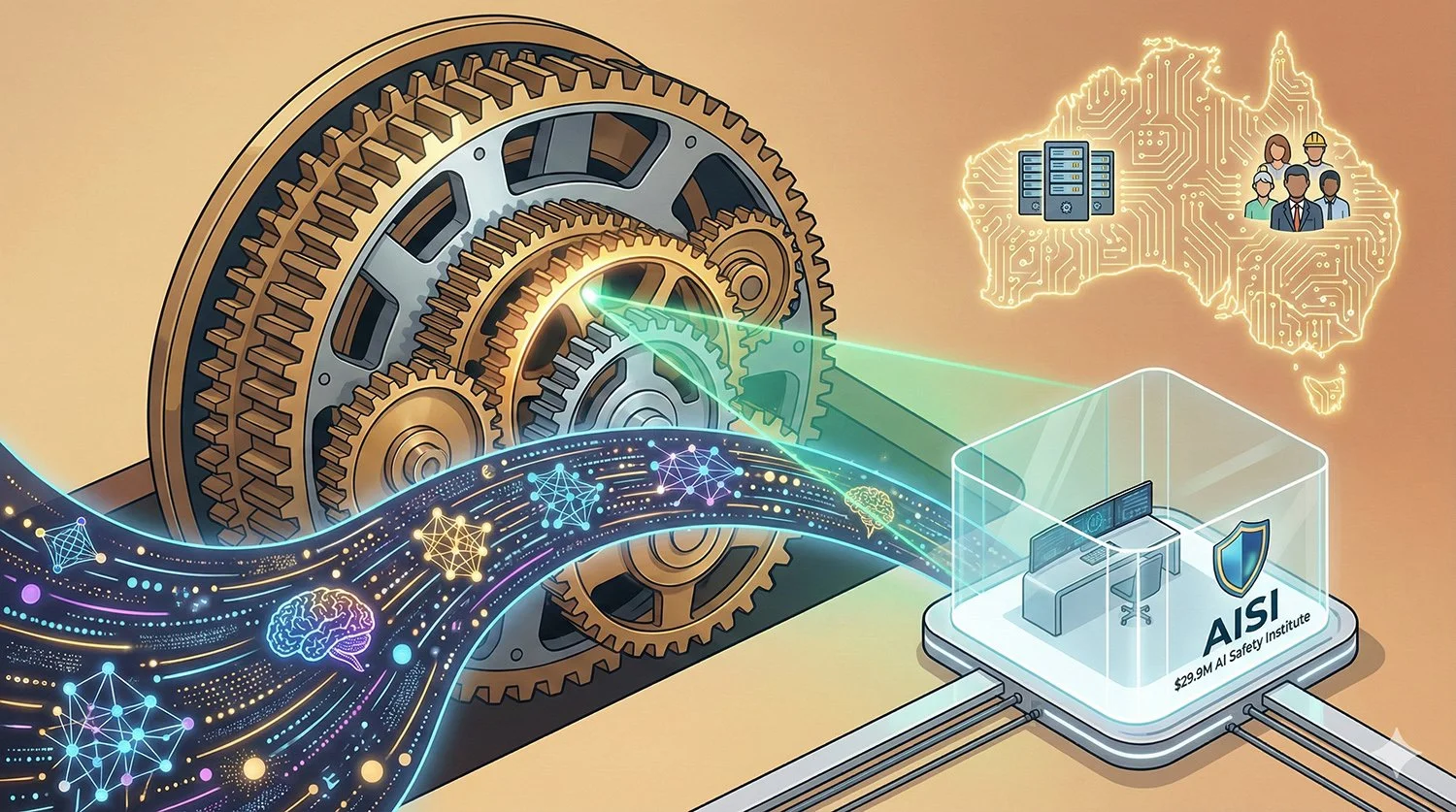

The United Kingdom government has expanded the remit of its Regulatory Innovation Office, adding robotics and defence technologies as new priority areas and pointing to autonomous inspection drones as a clear example of where regulation can become slow and costly when approvals sit across multiple regulators.

Outdated Regulatory Barriers

On 16 January 2026, the UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology announced that the Regulatory Innovation Office (RIO) will focus on cutting “outdated” and overlapping regulatory barriers that can delay robotics and defence products reaching real world deployment. The department highlighted use cases such as robots inspecting offshore wind turbines and autonomous vessels for maritime patrol, and it specifically referenced autonomous inspection drones as a case where a developer may face separate approvals across aviation rules, data protection, and sector specific safety requirements.

Alongside the policy direction, the government also launched a new business reporting channel called the RIO Front Door pilot, intended to collect examples of regulatory barriers directly from companies in defence technology and robotics. The pilot is designed as a short, experimental intake process, with the government stating it will run for about four weeks and is intended to inform an updated version by early summer 2026.

Reducing Duplicated Processes

Autonomous drones sit at the intersection of several risk domains at once. Modern systems often rely on AI for perception and navigation, such as object detection, obstacle avoidance, and route planning. That capability is precisely what makes drones useful for inspection, logistics and emergency response, but it is also what increases the regulatory surface area.

The UK framing is that “multi regulator” friction can emerge when the same operational deployment triggers:

Aviation safety approvals, including airspace integration and operational risk assessment.

Data protection and privacy compliance, particularly when sensors capture imagery of people or private property.

Sector specific safety rules, which vary depending on whether the drone is used in energy infrastructure, healthcare logistics, industrial sites, or defence.

The policy intent is not to remove these safeguards, but to reduce duplicated processes and unclear handoffs between regulators, so that developers are not forced to treat each approval track as a separate, sequential project.

Speeding up Approvals for Complex Drone Operations

While robotics and defence are newly added priority areas as of January 2026, RIO’s earlier work has already included drones and other autonomous technology as one of its initial focus areas. In its “One Year On” report (published 21 October 2025), RIO describes work with the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and other departments aimed at speeding up approvals for complex drone operations, especially those beyond a pilot’s direct line of sight.

Key details in that report are relevant to the current announcement because they show what “streamlining” can look like in practice:

The report identifies Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations as a major regulatory bottleneck, with inconsistent or slow approvals limiting higher value use cases.

It says the CAA introduced a single standard risk assessment process (SORA) for complex operations and that this “has already reduced approval times by more than 60%”.

It also notes government funding support for drone regulation work and a target for routine scaled BVLOS operations by 2027.

The same report describes regulators experimenting with AI to improve regulatory throughput, including CAA work to trial AI assistants and simulators to help approve new drone technologies safely.

The “Approval Stack” Problem

The UK government’s example of an autonomous inspection drone is useful because it highlights a common pattern in unmanned aviation.

An operator might be ready technically (airframe, sensors, autonomy software, remote pilot procedures) but still face a long lead time because approvals are not only about the aircraft. They include:

Operational permissions for the airspace and flight profile.

Evidence that the autonomy system behaves safely under edge cases.

Processes for incident reporting, cybersecurity, and software change control.

Rules for camera data collection, retention, and lawful basis, particularly for inspection in populated areas.

This is where RIO’s message is essentially systems oriented: if the approval journey requires multiple regulators to evaluate related risks, policy coordination can reduce duplicated evidence requests and reduce the chance that one regulator’s requirements unintentionally block another regulator’s pathway.

Front Door Intake plus Cross Regulator Focus

The new Front Door pilot is positioned as an early step that collects concrete barrier reports from industry, including which regulator is involved, what the product does, and how the barrier affects timelines or investment. The published guidance also sets expectations that submissions will be reviewed by sector teams and used to shape follow on reforms.

Separately, the January 2026 announcement signals that RIO will now explicitly apply this approach to robotics and defence technology, where autonomous drones are one of the most visible overlaps between AI, safety regulation, and national security priorities.

How This Compares with Australia, the EU, and the US

Even though the UK announcement is local, the underlying regulatory challenge is widely shared.

Australia: Australia’s CASA has recently updated an exemption that simplifies approvals for certain authorised operators flying drones over areas where many people are present, which reflects a similar theme: reducing friction for specific operational cases while maintaining safety controls.

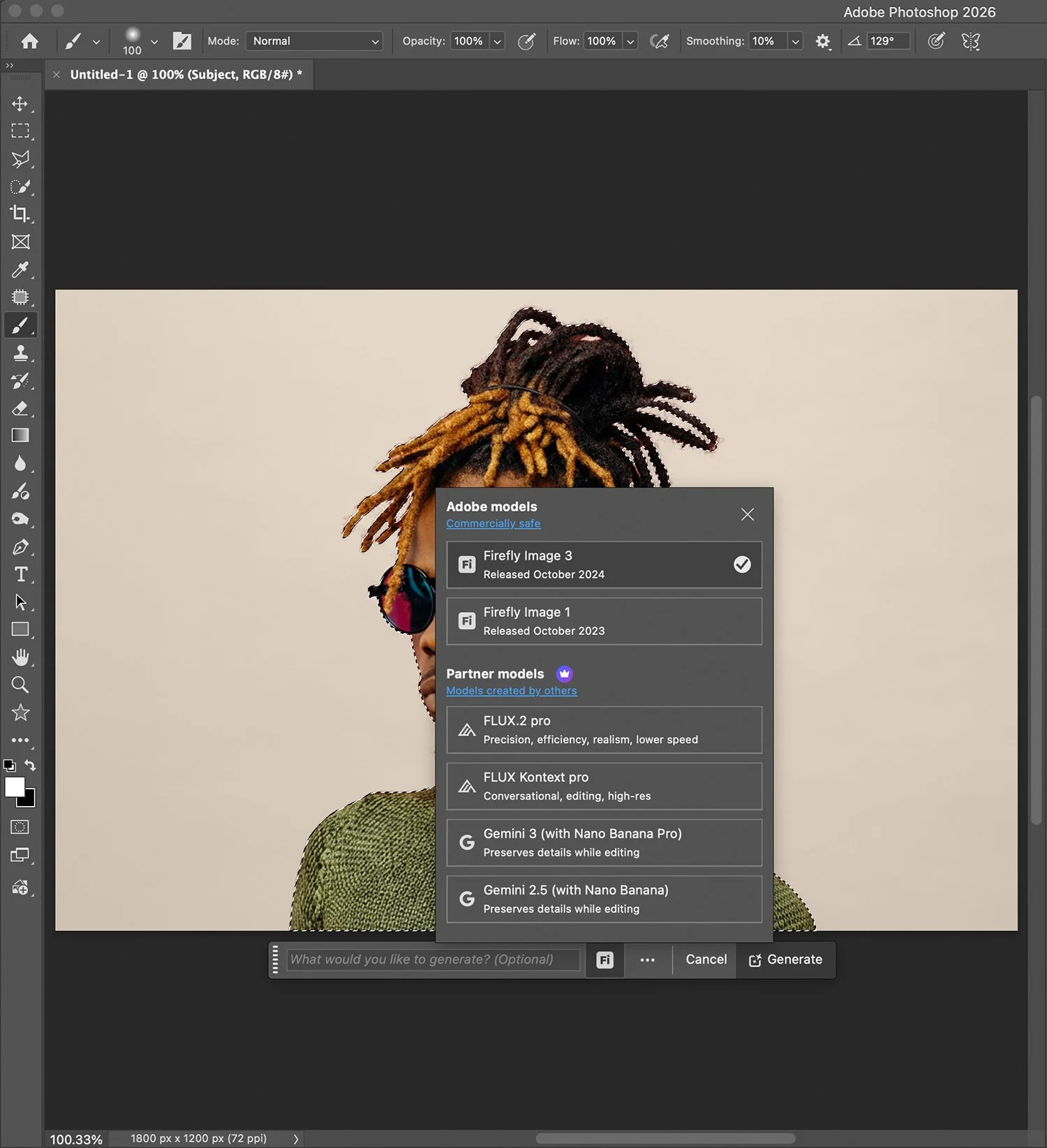

European Union: EASA has opened consultation on a proposal that aims to translate EU AI Act requirements into aviation specific guidance for “AI trustworthiness”. This is a different layer than flight permissions, but it speaks to the same question regulators face: how to validate safety relevant AI behaviour in high consequence systems.

United States: The US FAA published a proposed rule in August 2025 on normalising BVLOS operations with performance based regulations, signalling an effort to move away from case by case approvals for scalable commercial drone uses.

Taken together, the UK approach looks less like a single drone rule change and more like a governance mechanism designed to reduce duplication across regulators, while aviation authorities continue to refine BVLOS pathways and evidence requirements.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.