Hybrid AI Method Samples Rare Heatwaves 30-300x Faster Than Standard Models

Image Credit: Jacky Lee

A Nature News article published on Dec 11 reported on research that combines artificial intelligence with a conventional climate model to study extreme weather, aiming to estimate rare heat events faster than running the physics model alone. Nature said AI forecasting systems have improved rapidly, but can struggle to forecast extreme events they have not encountered in training data as the planet warms.

What Nature Reported

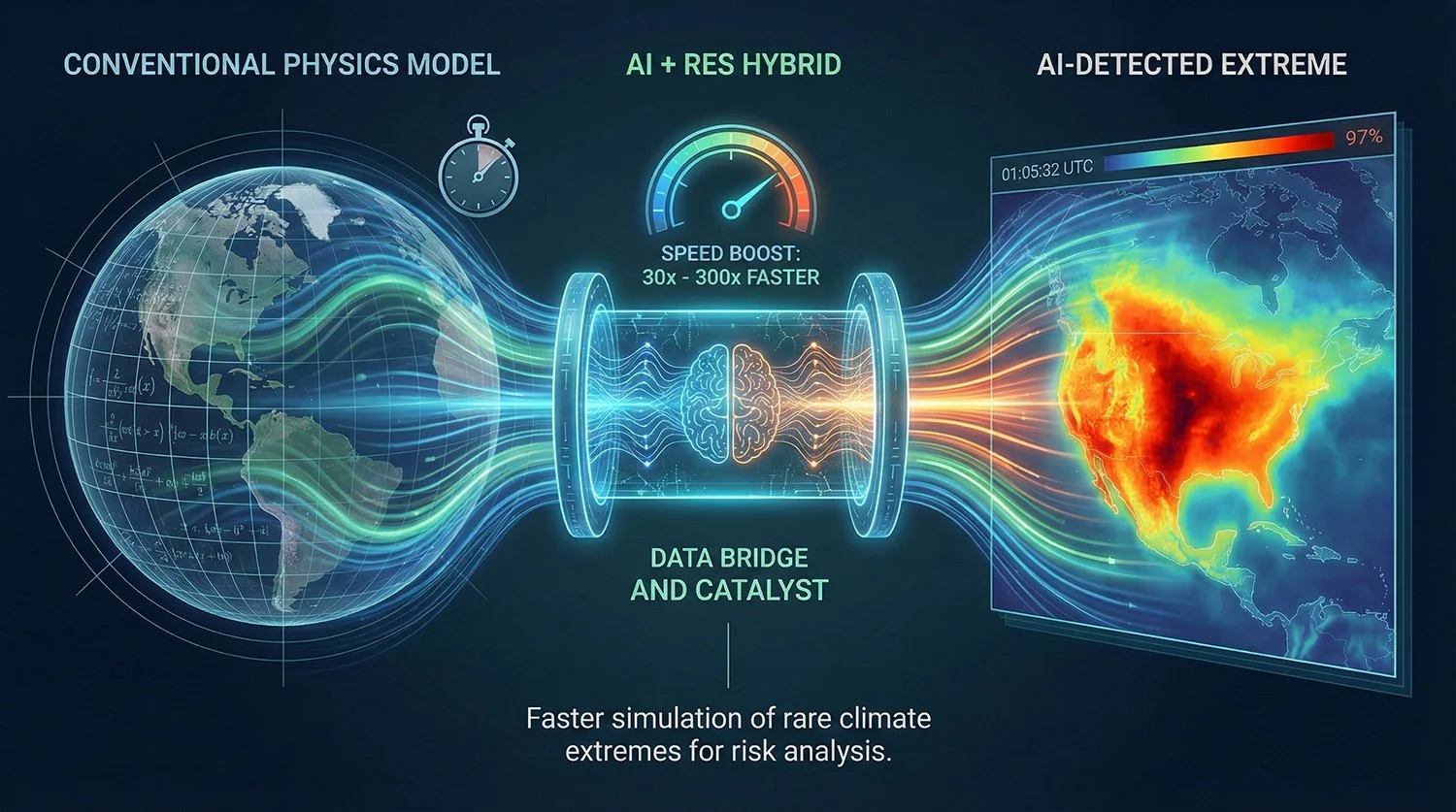

Nature described an approach that keeps a physics based climate model in the loop while using AI to accelerate the exploration of extreme outcomes, rather than replacing physical simulation entirely. The article was written by Alexandra Witze.

Nature’s summary framed the work around heatwaves in particular, describing the goal as predicting heatwaves faster than the standard model alone when AI is combined with a conventional climate model.

The Underlying Method and What It Actually Demonstrated

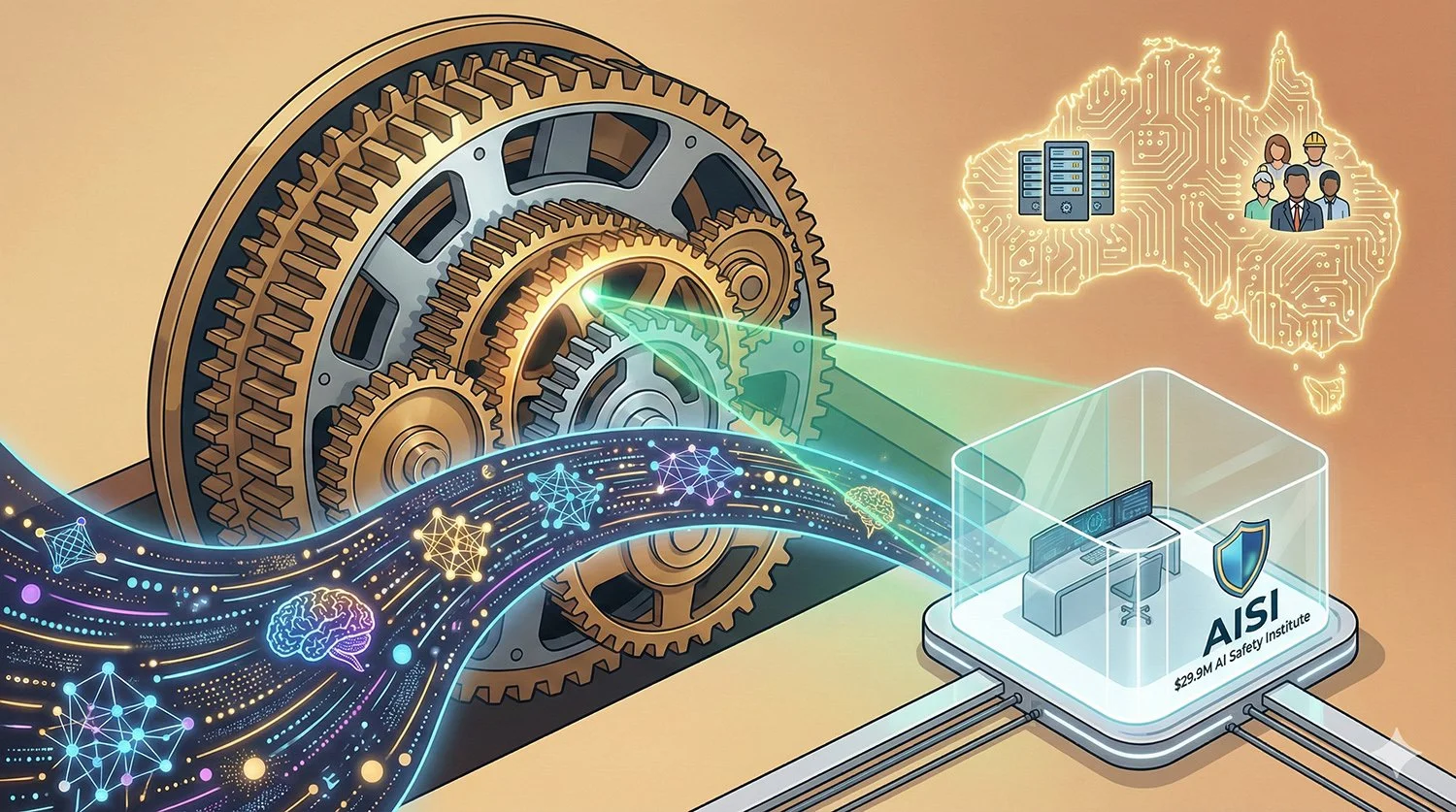

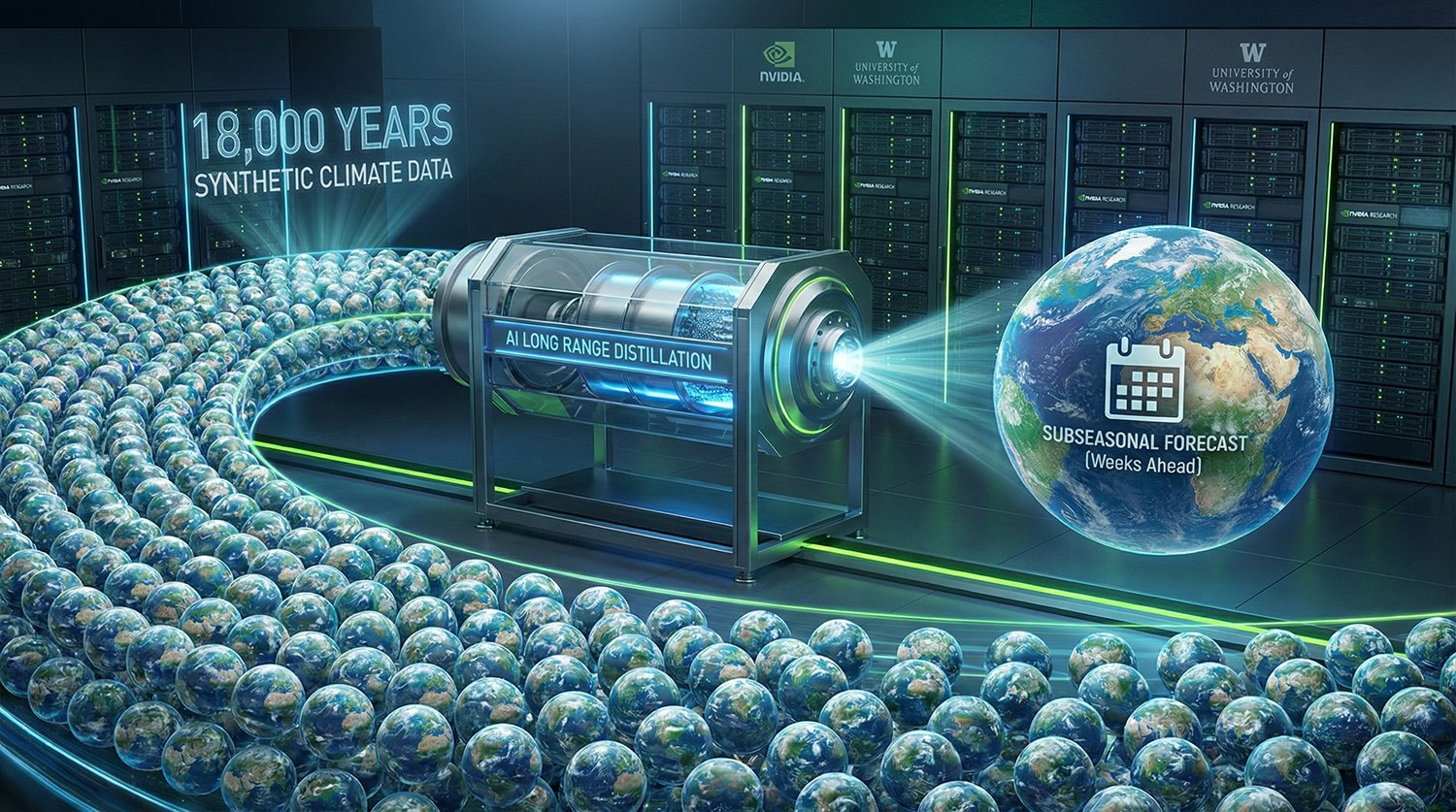

One of the main references in the Nature piece is a 2025 arXiv preprint titled “AI boosted rare event sampling to characterise extreme weather”, which presents an algorithm the authors call AI plus RES.

In the preprint abstract, the authors say AI plus RES uses ensemble forecasts from an AI weather emulator as a “score function” to guide rare event sampling of a physics based climate model, producing extreme weather statistics and associated dynamics at about 30 to 300 times lower computational cost than the baseline approach. They report the demonstration case as mid latitude heatwaves.

The same abstract sets out the motivation: observational records are too short and physics based global climate models are too computationally expensive to robustly sample the rarest extremes, while AI emulators can struggle on extremes that have few or no examples in their training data.

Why This Matters for AI Weather and Climate Risk

The work highlighted by Nature sits in a fast moving field where AI models are increasingly used for weather prediction, but where reliability on rare extremes is an open concern. Reuters has previously reported that AI is sharpening forecasts for hazards such as floods, while stressing that better predictions do not automatically prevent disasters without preparedness and action.

The hybrid approach reported by Nature targets a specific gap: efficiently characterising the tail risks that matter for planning, such as how often exceptionally severe heat events might occur, while anchoring those estimates to a physics based model rather than relying on pattern learning alone.

How It Compares with Other Prominent AI Forecasting Systems

Several leading systems focus on faster operational forecasting at weather timescales.

DeepMind’s GraphCast, published in Science in 2023, is a machine learning method trained on reanalysis data to forecast many weather variables out to 10 days.

DeepMind’s GenCast, published in Nature, is a probabilistic model aimed at producing ensemble style forecasts and uncertainty estimates, reported as more skilful and faster than a leading operational ensemble benchmark in the paper’s evaluation.

ECMWF has also developed the Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System, described by ECMWF as a new forecasting system, with ECMWF later announcing its AI forecasts becoming operational.

A separate stream of work aims at broader Earth system prediction. Aurora, published in Nature, is presented as a foundation model for the Earth system designed to tackle a variety of forecasting tasks.

By contrast, AI plus RES is presented as a way to accelerate rare event sampling for extreme statistics, demonstrated on mid latitude heatwaves, rather than as a general purpose public forecast system.

Local Decisions Depend on Local Hazard Detail

Australian climate risk work has repeatedly pointed to worsening hazards. CSIRO’s National Climate Risk Assessment material states that extreme heat, floods and bushfires will escalate health risks.

For decision making, agencies have also emphasised why “global” tools often need localisation. The Climate Change in Australia platform notes that global climate models have coarse resolution and cannot adequately represent weather scale phenomena at about 1 to 10 km, so downscaling methods are used.

The Australian Climate Service says downscaled climate projections provide hazard information at scales of less than 10 kilometres, intended to give more local detail for planning.

Against that backdrop, the research highlighted by Nature can be framed as part of a wider push to make extreme risk estimates more computationally feasible, but its direct applicability to Australian bushfire or flood decision tools would still depend on how the approach performs in higher fidelity regional systems and in locally relevant hazards beyond the heatwave test case reported in the preprint.

What to Watch Next

The Nature report and the arXiv reference point to an active research direction rather than a deployed operational service. The central questions for uptake are whether the approach scales to more complex models and regions, how uncertainty is communicated, and how results are validated when the target events are, by definition, rare.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.