TGA Permits Hypertension Claims for AI Wearables: New Rules

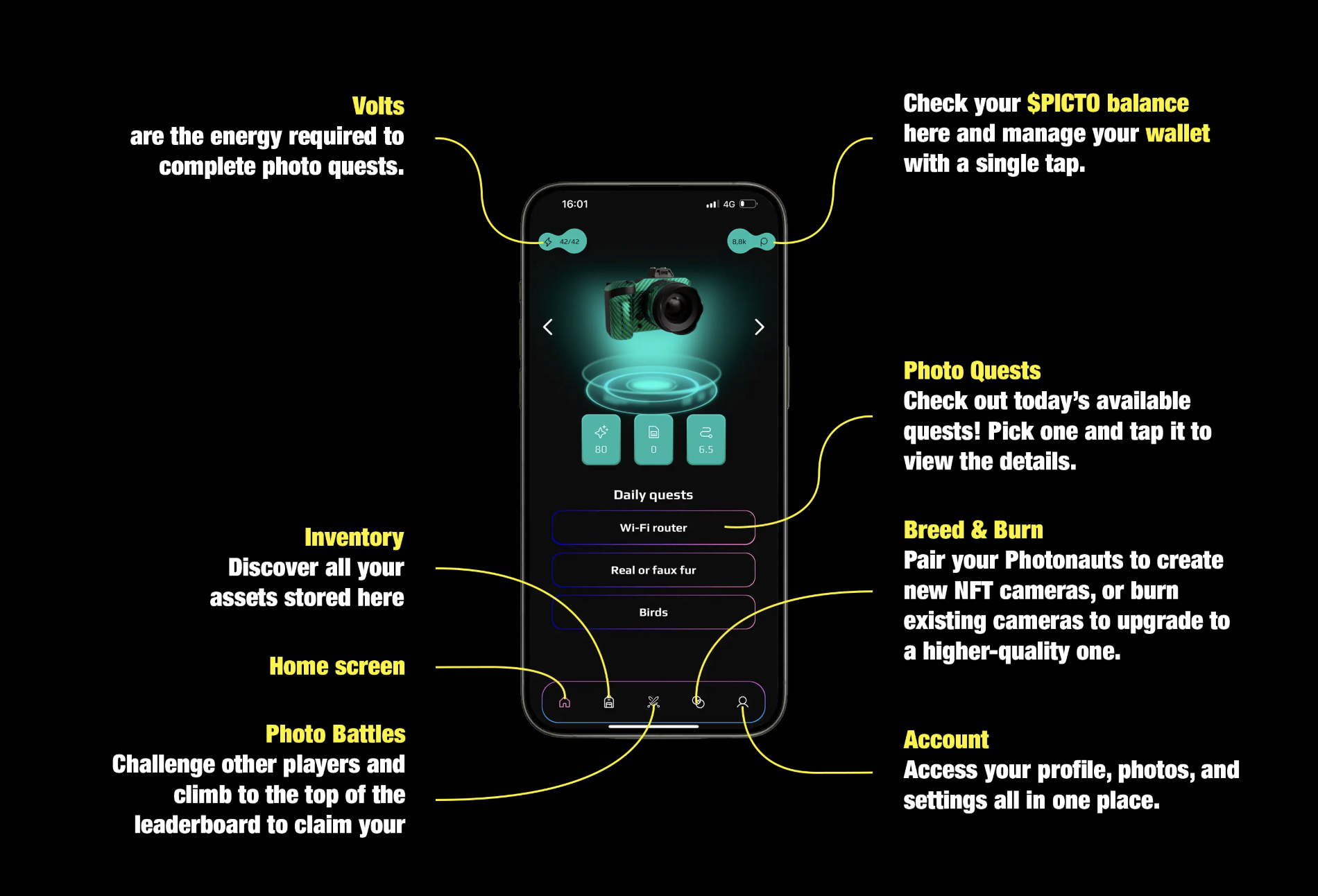

Image Credit: Mockup Graphics | Splash

Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration has issued a new advertising permission that narrowly allows certain hypertension related claims for a specific kind of software medical device: apps and devices that analyse photoplethysmography (PPG) data and notify users about patterns that are suggestive of hypertension.

The instrument is titled Therapeutic Goods (Restricted Representations — Hypertension Software) Permission 2026, dated 8 January 2026, and it commenced on 9 January 2026. It was made under section 42DK of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 by Tracey Lutton, a delegate of the Secretary of the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing.

Hypertension is a Controlled Term in Advertising

In Australia, advertising that references particular diseases or conditions can be a restricted representation, which generally requires prior approval or a permission before it can be used in advertising.

Hypertension is a good example of why this matters: it is common, serious when unmanaged, and easy to misunderstand when presented as a consumer facing feature in an app or wearable. The TGA’s permission does not change the underlying rule set. It creates a tightly controlled pathway so some hypertension related wording can be used, but only for specific medical devices and only with specific warnings and constraints.

What Products the Permission Actually Covers

The permission applies only to specified goods, defined as medical devices that:

are included in the ARTG (the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods)

are software only mobile medical applications, or non invasive medical devices that incorporate software

have an accepted intended purpose that involves identifying and notifying users of patterns from PPG data that are suggestive of hypertension

That definition is technology forward but product neutral. It does not name brands. It focuses on the function and the intended purpose accepted for ARTG inclusion.

Two Things Advertisers are Allowed to Say

The permission covers two types of statements.

1. Saying the software may identify patterns suggestive of hypertension

This is permitted only if the advertisement:

stays consistent with the device’s accepted intended purpose and any ARTG conditions

includes prominent advisory statements that:

if a pattern suggestive of hypertension is identified, the user should consult a medical practitioner

the absence of a notification does not exclude the presence of hypertension

does not include claims about accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, or limit of detection, unless those claims appear only in the instructions for use

That last condition is a big deal from an IT and AI lens. It effectively blocks marketing style performance language in ads, pushing any performance discussion into regulated instructions for use rather than promotional copy.

2. Using “hypertension” in the product name

This is permitted only if the advertisement:

stays consistent with the accepted intended purpose and ARTG conditions

includes a prominent advisory statement that the notification feature does not replace advice or assessment from a qualified healthcare professional

Notably, the “no accuracy or sensitivity claims” restriction is explicitly stated for item 1, not item 2.

Where the AI angle sits in Australia’s regulatory framing

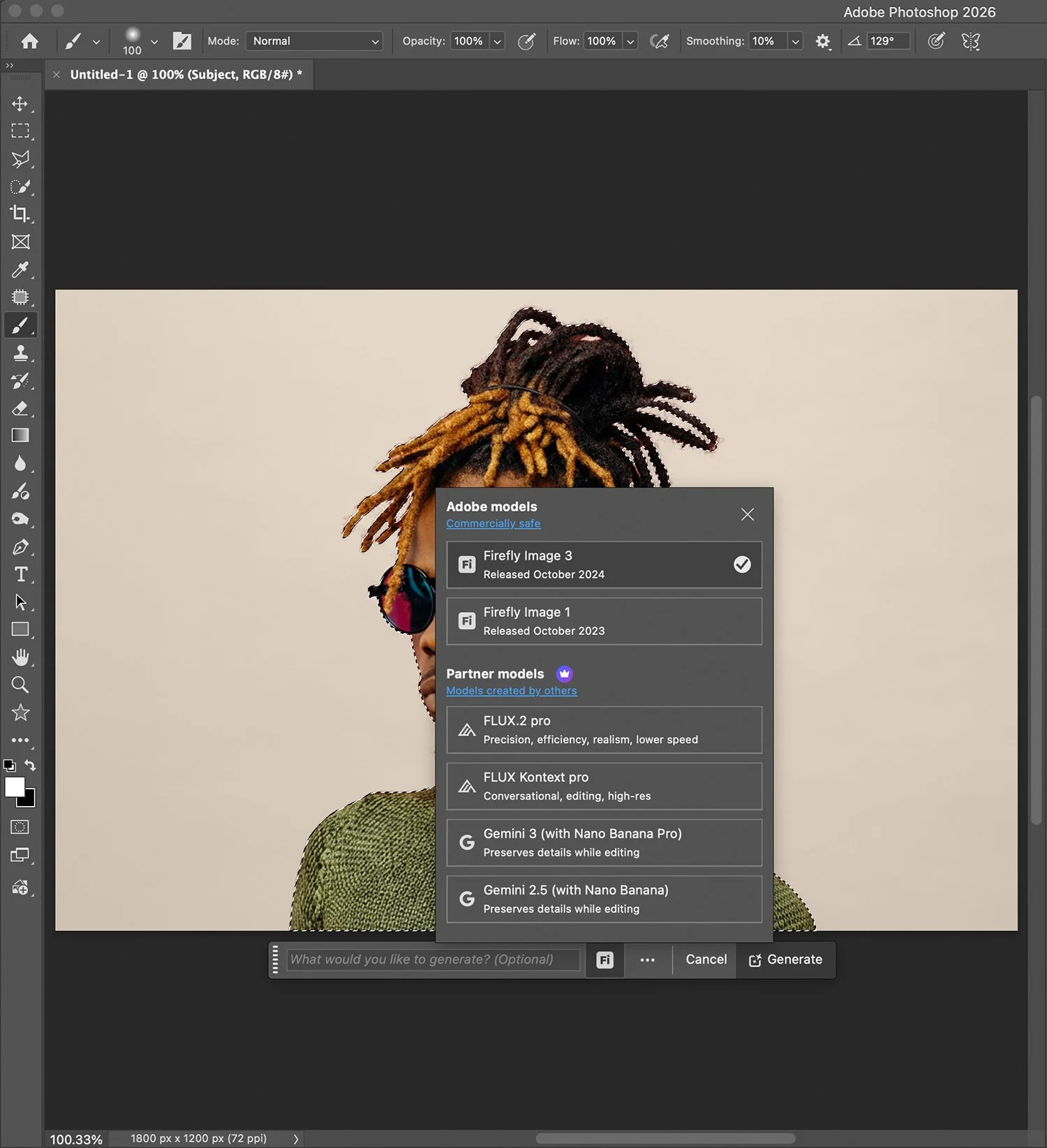

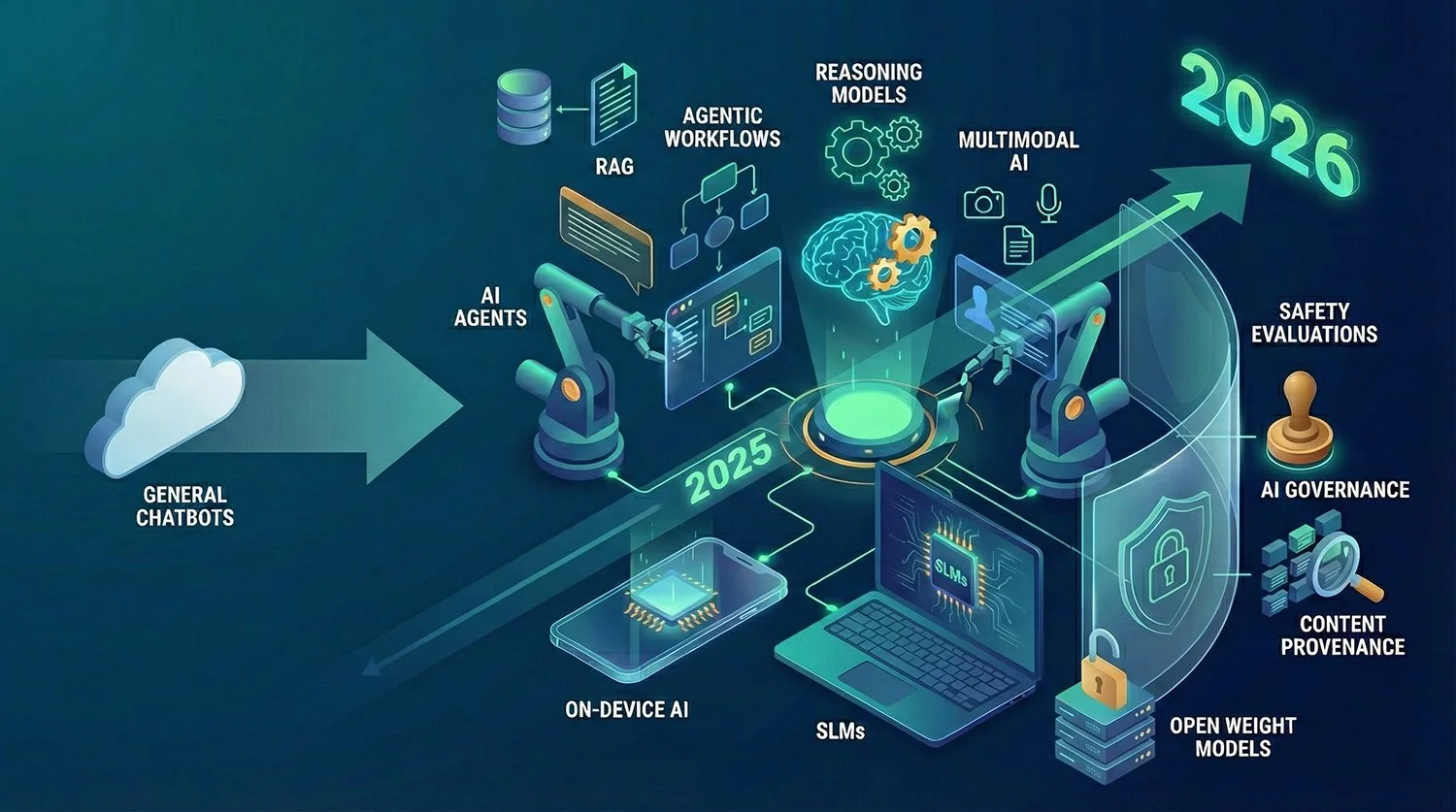

The permission itself is written in clinical and legal terms, but it sits squarely in the world of AI enabled consumer health software.

The TGA’s own guidance explains that AI and software can be regulated as a medical device when it is intended for purposes such as diagnosis, monitoring, prediction, prognosis, or investigation of a physiological process.

In practice, PPG pattern analysis for hypertension risk signalling is often implemented using machine learning, especially when the feature is designed to work passively over time and across noisy real world signals. The permission does not mandate a particular technique, but it recognises the category: software that interprets biosignals and issues a health related notification.

How This Compares with Similar Australian and Overseas Moves

Australia: TGA’s earlier “Sleep Apnoea Software” permission

In 2025, the TGA issued a similar permission for software that identifies patterns suggestive of sleep apnoea. Like the hypertension instrument, it is built around advisory statements and strict boundaries on what the feature is and is not.

A key difference is tone and positioning: the sleep apnoea permission is very explicit that the goods are not intended for screening, diagnosis, treatment or management of sleep apnoea, alongside “consult a medical practitioner” prompts.

The hypertension permission instead focuses on “patterns suggestive of hypertension”, consultation advice, and a clear reminder that a lack of notification does not rule hypertension out.

United States: FDA listing for a hypertension machine learning notification feature

The US FDA’s public 510(k) database includes an entry for Hypertension Notification Feature, classified as Hypertension Machine Learning Based Notification Software (K250507), with Apple listed as applicant.

This does not directly map to Australian advertising permissions, but it shows the same broad product category emerging in multiple jurisdictions: software that uses biosignal data and machine learning to raise a hypertension related flag for users.

What It Means for Australians

For consumers

You are likely to see more carefully worded marketing around hypertension notifications from wearable connected software that is included in the ARTG. The required statements are designed to keep the message grounded: notifications are a prompt to seek proper assessment, and silence is not a clean bill of health.

For developers and advertisers

If you are building or promoting PPG based hypertension notification software in Australia, this permission is a reminder that:

disease terms are controlled in advertising, and you need the right regulatory basis to use them

marketing style performance claims (accuracy, sensitivity, and similar) are exactly the sort of thing regulators want out of ads for this category

For the broader medical AI landscape

This is another example of regulators trying to strike a middle ground: acknowledging consumer health AI is here, while shaping how it is described to the public to reduce the risk of overconfidence, misinterpretation, or delayed care. It also aligns with Australia’s wider policy work on safe and responsible AI in healthcare.

License This Article

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.