Prithvi CAFE: Hybrid AI Blends Tech to Improve Satellite Flood Mapping

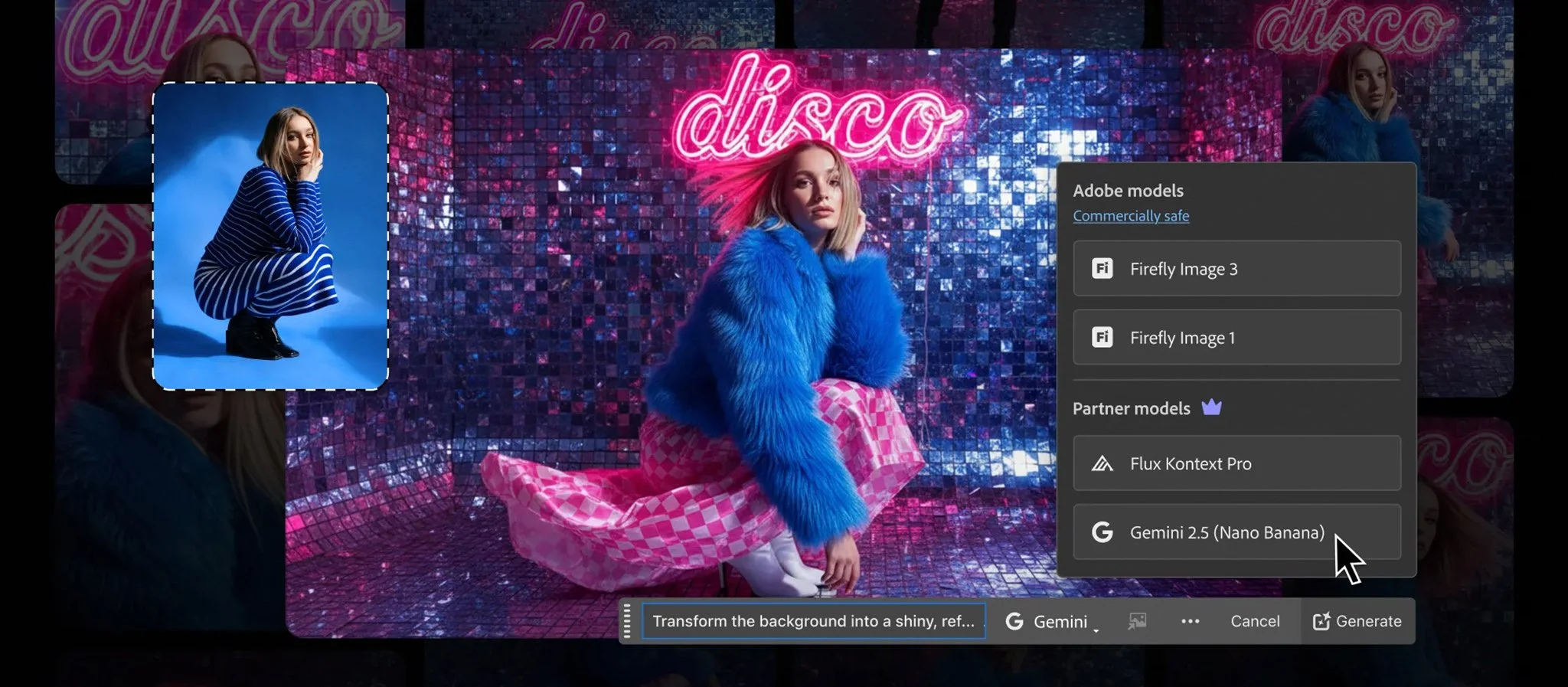

Image Credit: Evelyn Geissler | Splash

A new research paper posted on arXiv on 5 January 2026 describes an AI system called Prithvi CAFE. Its job is simple to explain: look at satellite images and colour in the areas that are likely underwater after a flood.

The authors are Saurabh Kaushik, Lalit Maurya, and Beth Tellman. In the paper, Kaushik and Tellman list their affiliation as the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE), University of Wisconsin Madison, while Maurya lists Portsmouth AI and Data Science Centre (PAIDS), University of Portsmouth.

The arXiv record also states the work was accepted at the CV4EO Workshop at WACV 2026.

Flood Mapping from Space is still Tricky

Satellites are great for seeing huge areas quickly, but floods are not always obvious in images:

Cloud and haze can hide the ground.

Shadows and dark surfaces can look like water.

The “edge” of water can be messy, especially around vegetation and buildings.

A model trained on one country or flood type can struggle when used somewhere new.

That last point is important. In the real world, emergency teams need a system that still works when the next flood happens somewhere the model has never seen before.

What is Prithvi?

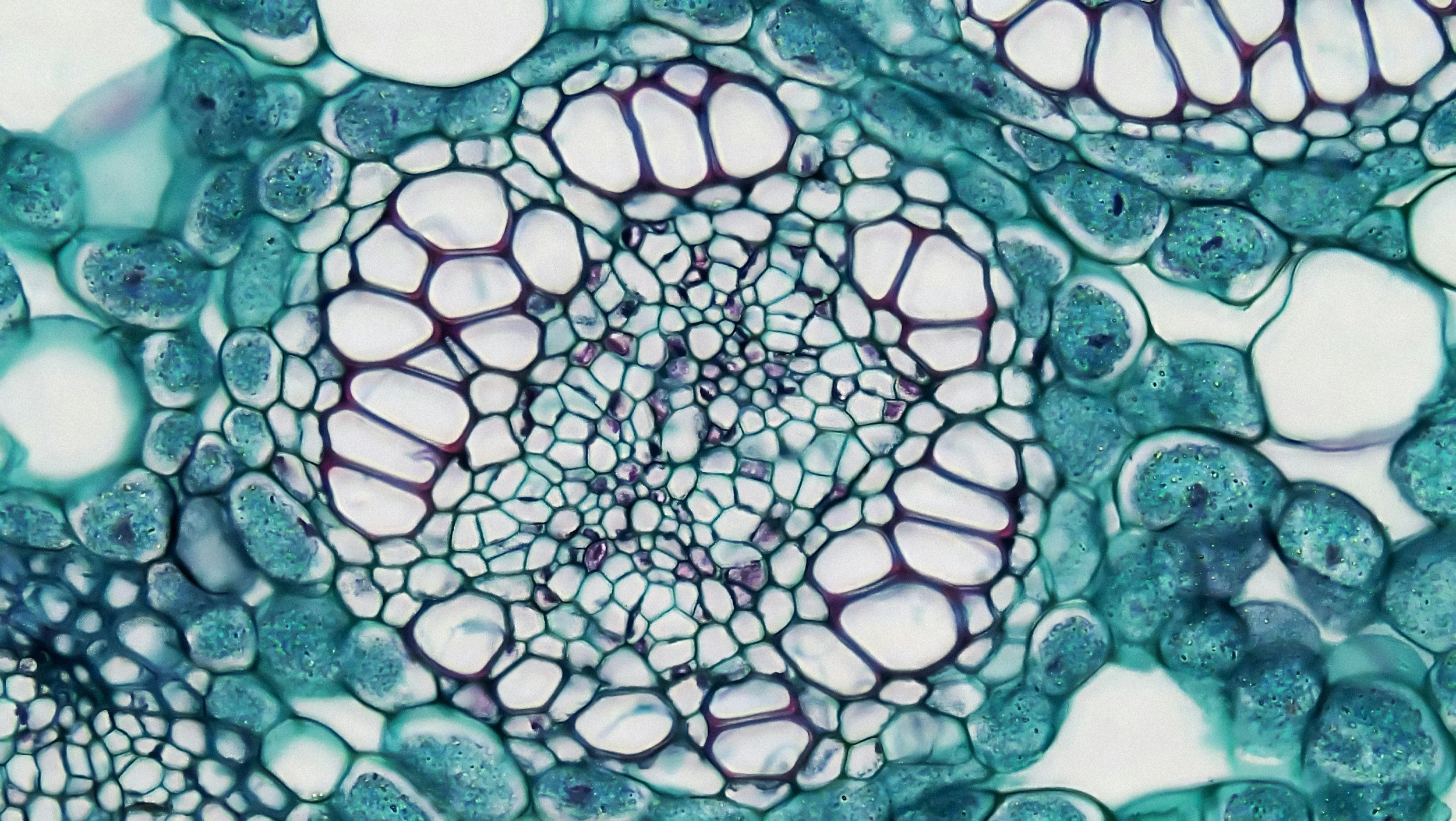

This research builds on Prithvi EO 2.0, a widely used “foundation” AI model for Earth observation. Think of Prithvi as a big, general purpose “brain” trained on lots of satellite data so it can be adapted to many tasks, like land cover mapping, crop monitoring, or flood detection.

Prithvi was trained to understand six specific types of light (six satellite bands) often used in remote sensing, rather than normal red green blue photos. That helps it recognise patterns humans cannot easily see.

What Prithvi CAFE Changes?

The researchers argue that the “big brain” approach can sometimes miss fine detail when drawing flood boundaries. So they combine two styles of AI in one system:

A large Prithvi based part to understand the bigger picture across the scene.

A smaller “detail focused” part (a CNN) to sharpen edges and local patterns.

Then the system blends the two streams before producing the final flood map.

It is like using one tool to understand the whole landscape, and another tool to trace the outlines more carefully, then merging both to produce the final map.

The “Lighter Weight Training”

Training huge AI models from scratch is expensive. This paper tries to reduce cost by using a technique where the main Prithvi model is mostly kept as is, and the system learns only smaller add ons.

In their reported setup, the authors say they train about 45.5 million parameters, compared with the much larger size number listed for the Prithvi baseline in their tables (650 million). In simple terms: they try to tune a smaller part of the system, rather than re-training everything.

For organisations with limited computing budgets, that kind of approach can make the difference between “research only” and “actually deployable”.

What Data They Tested on?

To check whether the model is any good, they used two well known flood mapping datasets.

Sen1Floods11

Sen1Floods11 is a public dataset built from Sentinel satellite data for training and testing flood mapping algorithms. The original dataset paper describes 4,831 image chips (small cut outs of larger satellite scenes). The Prithvi CAFE paper uses the standard evaluation split and also reports a special test where the model is checked on a location held out during training.

FloodPlanet

FloodPlanet is a flood dataset labelled using PlanetScope imagery, which is higher resolution (about 3 metres per pixel) than many free satellite sources. The public release is commonly described as 366 labelled chips across 19 flood events worldwide. In this paper’s experiments, the authors report using 298 Sentinel 2 images paired with PlanetScope derived labels, resized to 320 by 320, and tested using 4 fold cross validation (a common way to rotate training and testing across the dataset).

The Results?

The paper reports accuracy using IoU (intersection over union), which can be understood as how much the AI’s predicted flood area overlaps with the flood area labelled by humans. A higher score means better performance.

Sen1Floods11 (standard test)

Prithvi CAFE: 83.41

Prithvi baseline: 82.50

Prithvi CAFE improves over Prithvi and several other foundation model baselines, while strong classic models are still very competitive on standard splits.

Sen1Floods11 (new place test: Bolivia)

This is where the paper shows its clearest advantage. It reports:

Prithvi CAFE: 81.37

U Net baseline: 70.57

Prithvi baseline: 72.42

It seems to hold up better when moved to a new region the model did not train on, at least in this test.

FloodPlanet

On FloodPlanet, their table reports:

Prithvi CAFE: 64.70

Prithvi baseline: 61.91

U Net baseline: 60.14

The Bigger Trend in “AI for Earth”

There is a growing push to use large “general purpose” satellite AI models as a starting point, then adapt them to specific jobs like floods. But recent benchmarking research has also pointed out a reality check: bigger is not always better on every dataset, especially when you need sharp boundaries.

Prithvi CAFE is part of the practical response: keep the foundation model benefits, but add design choices that aim to make the output cleaner and more reliable for flood boundaries.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.