10,000 Users Rate Political Bias Across 24 Major AI Models

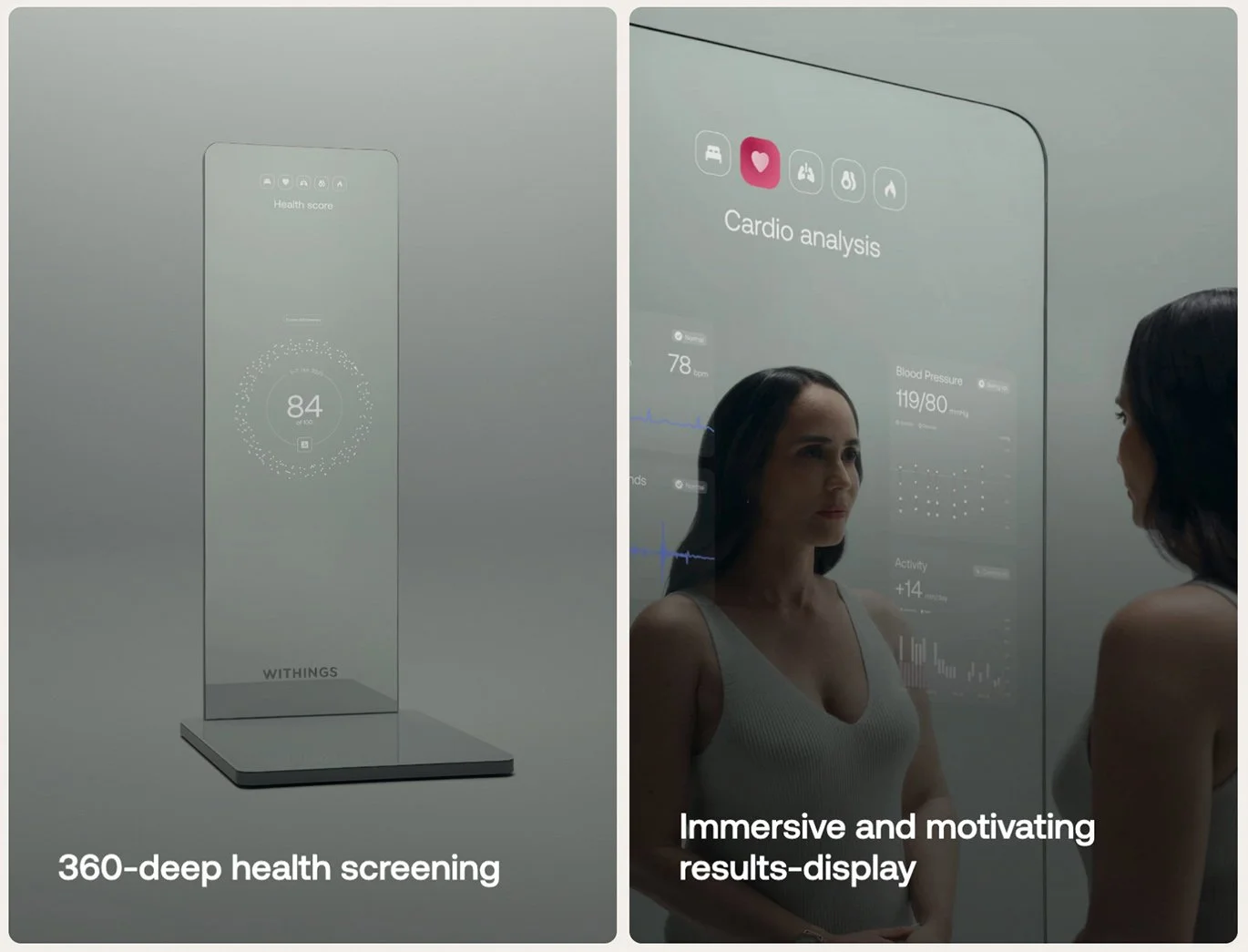

AI-generated Image (Credit: Jacky Lee)

Large language models (LLMs) that power chatbots and writing assistants continue to show systematic social and political biases, according to a growing body of research and emerging regulatory scrutiny. Recent studies suggest these systems not only inherit imbalances from their training data but, in some cases, can subtly nudge users toward particular viewpoints, raising concerns for democratic debate, hiring and online information ecosystems.

The findings, published between 2024 and late 2025, build on earlier warnings that models trained on vast collections of internet text can reproduce stereotypes and ideological leanings. While major developers have added safety layers intended to keep outputs “neutral”, evidence shows these guardrails themselves encode value judgments, making it difficult to separate technical design choices from broader social and political questions.

Background: How Training Data Imprints Values

LLMs are trained on enormous corpora of books, websites, code and other text, much of it scraped from publicly available sources. This breadth gives models wide-ranging knowledge but also exposes them to the same patterns of exclusion and bias found in online discourse and media.

Research has repeatedly documented how these patterns surface in model outputs. For example, work presented at ACL and related venues has shown that large models frequently generate gender-stereotyped personas and associate different traits, roles and competencies with “male” and “female” prompts, even when explicitly asked to avoid bias. Similar studies have found that models sometimes reproduce racial and ethnic stereotypes embedded in their training corpora, and that mitigations such as data filtering or post-hoc output adjustments only partially address the problem.

When such systems are integrated into products like search assistants, résumé screeners or content recommenders, these statistically learned patterns can be perceived as neutral advice, even though they reflect skewed or incomplete views of society.

New Evidence on Political Leanings

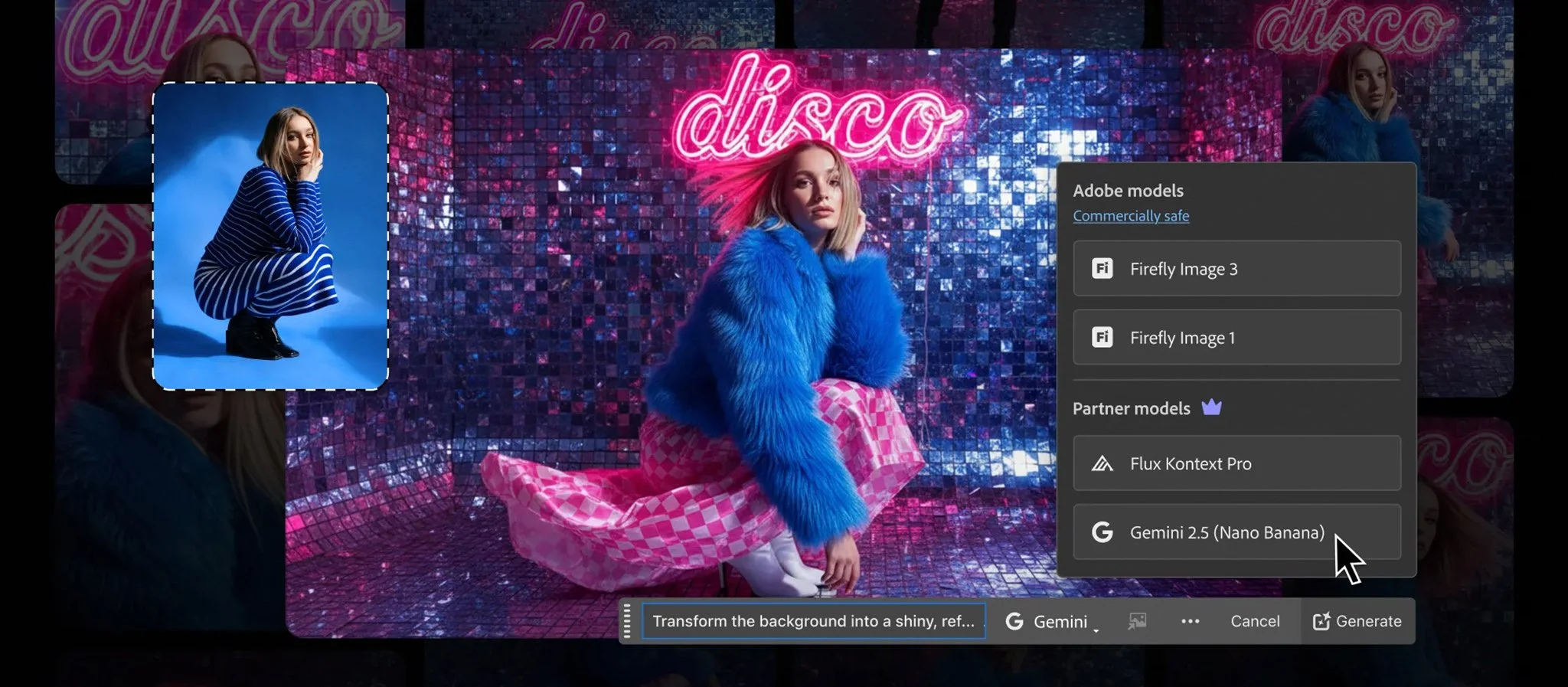

One of the most detailed cross-model comparisons so far comes from a 2025 working paper by researchers at Stanford University and the Hoover Institution, led by political scientist Andrew B. Hall. The team asked over 10,000 U.S. adults to rate answers from 24 different LLMs, built by eight companies, to political questions spanning dozens of topics. In total they collected more than 180,000 evaluations.

Across most topics, participants perceived the majority of models as left-of-center compared with the average U.S. adult. OpenAI’s models were generally rated as the most left-leaning, while Google’s models tended to appear closer to the political center. Some open-source systems, including certain Llama variants, occasionally appeared slightly right-leaning on economic issues.

Anthropic, the U.S. firm behind the Claude family of models, has been running its own internal audits. In a mid-November 2025 blog post, the company described “political even-handedness” tests for Claude Sonnet 4.5 that compared how the model responded to prompts framed from opposing ideological perspectives. According to Anthropic’s metrics, Sonnet 4.5 gave responses judged as roughly even-handed in most cases and slightly outperformed OpenAI’s GPT-5 and Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro on this internal benchmark.

Anthropic emphasised that the evaluation focuses on balance between pre-defined “left” and “right” framings in English and does not guarantee neutrality across all cultures, languages or issues. External researchers similarly caution that perceptions of bias depend heavily on who is asked to judge the outputs and which political spectrum is used as a reference.

From Static Bias to Active Persuasion

Beyond measuring where models sit on a left-right axis, researchers are increasingly examining how LLMs might influence users’ views.

A study now published in Nature Human Behaviour, originally circulated as a preprint in March 2024, asked U.S. participants to read arguments on controversial policy issues such as climate change and immigration. In debates where GPT-4 wrote one side and humans wrote the other, personalised GPT-4 arguments were more persuasive than human ones about 64% of the time.

The result suggests that, when used to generate targeted political messaging, advanced models could be highly effective persuaders. Media coverage in 2025 highlighted this as evidence that LLM-powered systems could substantially shape public opinion if deployed at scale in campaigns or issue advocacy.

Other work has looked at more mundane settings. An ACL 2025 paper on LLM-mediated discussion found that when a chatbot consistently framed urban planning and zoning debates in more pro- or anti-development terms, participants’ stated preferences shifted modestly but significantly toward the model’s framing after repeated interactions.

These experiments echo broader concerns about generative AI’s role in information operations. In 2025, U.S. authorities sanctioned Russian and Iranian groups for running influence campaigns that used AI-generated news sites and synthetic media to target voters, including content built with custom text and video models.

Bias Beyond Politics: Hiring and Job Platforms

Bias in LLMs is not limited to party politics. It also appears in automated recruitment tools, job ads and other decision-support systems.

A study led by Kyra C. Wilson and Aylin Caliskan at the University of Washington examined language-model-based résumé screeners that ranked otherwise similar applications differing mainly in the implied race and gender of the candidate’s name. In one configuration, the system preferred résumés with white-associated names in roughly 85% of comparisons and selected those with Black-associated names as top matches in only around 9%, indicating strong demographic skew.

A 2025 article in AI & Society argued that chatbots used in HR contexts can act as “gender bias echo chambers”, reinforcing stereotypical language around leadership, competence and emotional traits unless carefully constrained.

Outside résumé screening, regulators are beginning to act. In November 2025, France’s equality watchdog, the Défenseur des droits, found that Facebook’s job-ad delivery algorithm indirectly discriminated on the basis of sex after adverts for roles such as mechanics and pilots were shown predominantly to men, while preschool teaching roles were shown mainly to women. Meta disputed the decision but has been asked to adjust its systems.

Taken together, these examples show how language-based systems can turn subtle statistical patterns into concrete disadvantages for certain groups, whether in who sees which job ad or whose application is prioritised.

How Safety Training Shifts the Centre Line

Developers typically add several layers of “alignment” or safety training on top of base LLMs. Techniques such as reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) and “constitutional” training, where models are steered using written principles about acceptable behaviour, aim to reduce harmful content and keep outputs within broadly acceptable norms.

However, these safeguards implicitly encode value judgments: deciding which statements about religion, gender or politics are considered harmful or “unhelpful” is itself a normative choice. Anthropic’s political even-handedness work notes that safety interventions can sometimes “over-correct”, making a model more comfortable defending some positions than others, depending on the principles and examples used.

The Stanford–Hoover paper similarly concludes that differences across models partly reflect each company’s decisions about training data, content filters and alignment procedures, not just the raw internet text they ingest. From a user’s perspective, it is the combined effect that matters: people interact with a finished system whose responses already incorporate those choices.

Researchers say this does not mean companies are deliberately embedding partisan agendas, but it underlines that seemingly technical tuning decisions can have political and social consequences.

Regulatory Responses and the “Digital Omnibus”

Governments and international organisations are beginning to respond, though rules are still catching up with the technology.

UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, adopted unanimously by its 193 member states in 2021, calls for AI systems to respect human rights, avoid discrimination and include mechanisms for redress. It encourages impact assessments and external audits, but detailed implementation is left to national authorities.

In Europe, the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, often described as the first comprehensive horizontal AI law, entered into force in 2024 and is being phased in through 2027. The Act classifies uses such as biometric identification, credit scoring and certain employment and education tools as “high-risk,” subjecting them to obligations including fundamental-rights impact assessments, quality-management systems and post-market monitoring.

For the most serious infringements, such as prohibited AI practices, companies can face fines of up to €35 million or 7% of global annual turnover, whichever is higher.

In November 2025, the European Commission proposed a “Digital Omnibus” package that would, among other changes, delay some compliance deadlines for high-risk and general-purpose AI systems to allow more time for harmonised technical standards and enforcement capacity. The proposal followed lobbying from industry and concerns from several member states about implementation timelines.

Elsewhere, a patchwork of sector-specific rules is emerging. Some jurisdictions have introduced or proposed requirements for algorithmic bias audits in employment and credit scoring, while electoral authorities and foreign-policy bodies are exploring safeguards against AI-generated disinformation and foreign influence operations.

Gaps and Next Steps

Across the research and policy landscape, several recurring themes stand out:

Limited geographic and cultural coverage. Political-bias audits often focus on U.S. left-right scales and English-language queries. Studies presented at ACL and other conferences highlight that models may behave differently in non-Western languages and political contexts, underscoring the need for multilingual, multi-country evaluations that capture how systems treat religious minorities and Global South perspectives.

Post-deployment monitoring is still rare. A survey of AI-safety literature and company practices finds that most efforts still concentrate on pre-deployment mitigation rather than monitoring real-world impacts over time, especially once models are embedded in complex products such as social networks or enterprise platforms.

Human oversight can be weak in practice. While documents such as UNESCO’s recommendation and the EU AI Act stress meaningful human control, case studies in hiring and content moderation show that managers and moderators often defer to AI recommendations, particularly under time pressure or when performance metrics emphasise speed and volume.

Independent audits and transparency are key. Many scholars and civil-society groups advocate for regular third-party audits of high-impact systems, public disclosure of evaluation methods and clearer information to users about a model’s known limitations and tested biases. Initiatives around model cards, system cards and public benchmarks are seen as steps in this direction, though coverage remains uneven across providers.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.