AI Safety Gaps in GP Clinics: University of Sydney Study Warns of Regulatory Lag

Image Credit: Jacky Lee

A University of Sydney news release dated 17 December 2025 says artificial intelligence is already showing up in primary care through tools such as ChatGPT, AI scribes and patient facing apps, but argues evaluation and regulatory oversight are not keeping pace. The release points to a research review in The Lancet Primary Care that synthesised evidence across multiple regions and concludes many tools are being deployed without thorough evaluation or oversight.

What the Research Looked at

According to the University’s summary, the paper synthesised global evidence on how AI is being used in primary care across regions including the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, as well as parts of Africa, Latin America and Ireland. It describes common uses such as clinical queries, documentation support (including digital scribes), and patient advice via apps, then argues that evidence for real clinical effectiveness and safety often lags behind adoption.

The release quotes study lead Associate Professor Liliana Laranjo (Westmead Applied Research Centre) saying AI may ease pressure on overstretched services, but without safeguards there is risk to patient safety and quality of care.

Adoption Signals in Australia and Why They Are Hard to Measure

The University release says Australian uptake is “not reliably known” and cites an estimate of 40 percent. That figure is consistent with an RACGP newsGP weekly poll (3–10 November 2025, 1516 votes) where 40 percent of respondents reported they were currently using AI scribes in general practice. It is useful as a signal that interest is real, but it is not a representative national usage study and it measures scribes specifically, not all forms of generative AI use.

That measurement gap matters because it makes it harder to answer basic governance questions that health systems usually want before broad rollout, such as which tools are being used, in which settings, what data flows are involved, and how incident reporting is handled.

Where the Risks Show Up in Day To Day Practice

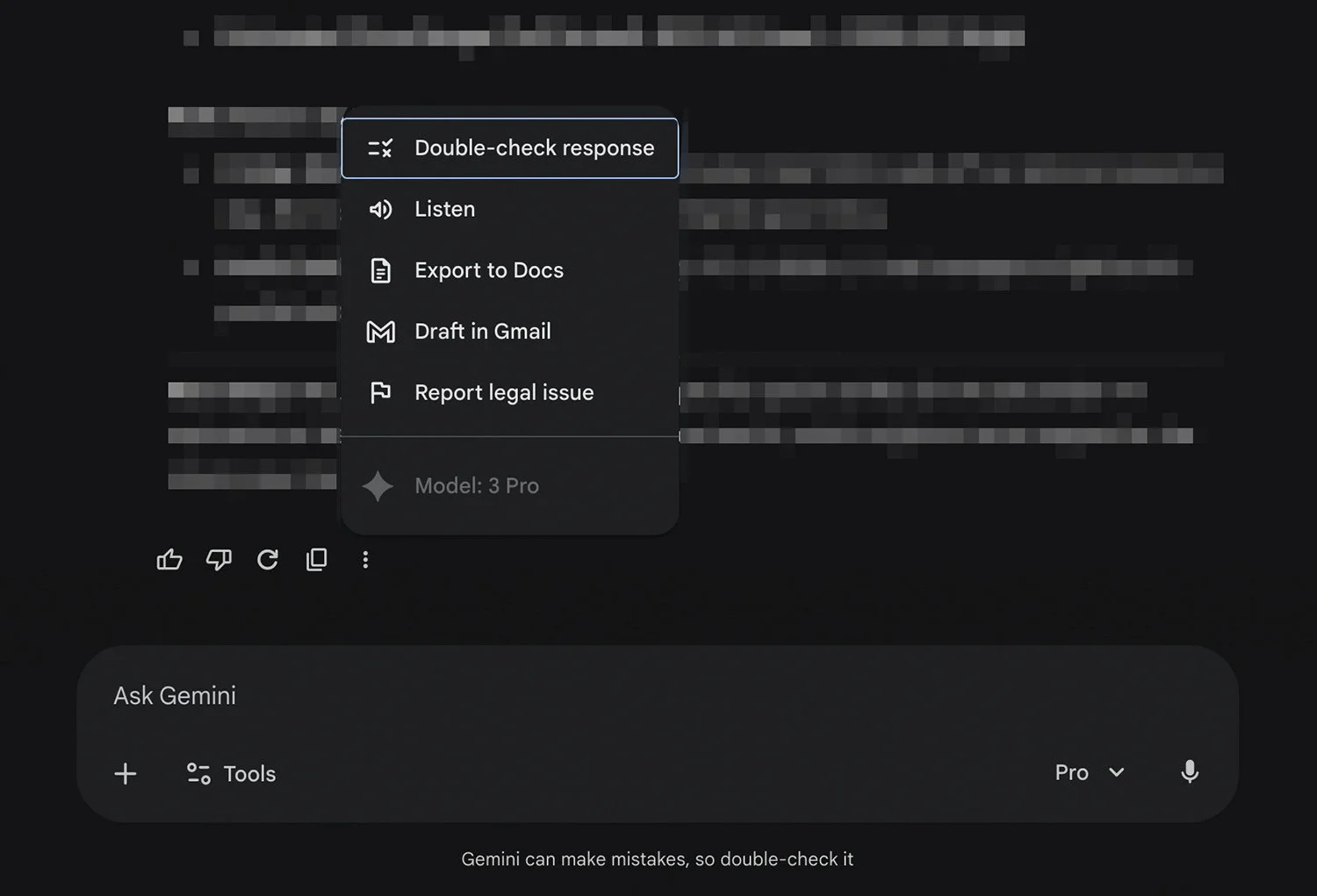

The release highlights a familiar pattern seen across generative systems: outputs can read confidently while still being wrong. It also says AI scribes and ambient listening tools may reduce cognitive load and improve job satisfaction, but can introduce automation bias and may miss social or biographical details that clinicians consider important context.

On the patient side, it points to symptom checkers and health apps as a fast growing category that often claims convenience and personalisation, while accuracy varies and independent evaluation is not always possible.

What Australian Regulators and Safety Bodies Are Saying Now

Australia already has moving pieces that map neatly onto the concerns raised in the University release, especially around when an AI tool becomes a regulated medical product.

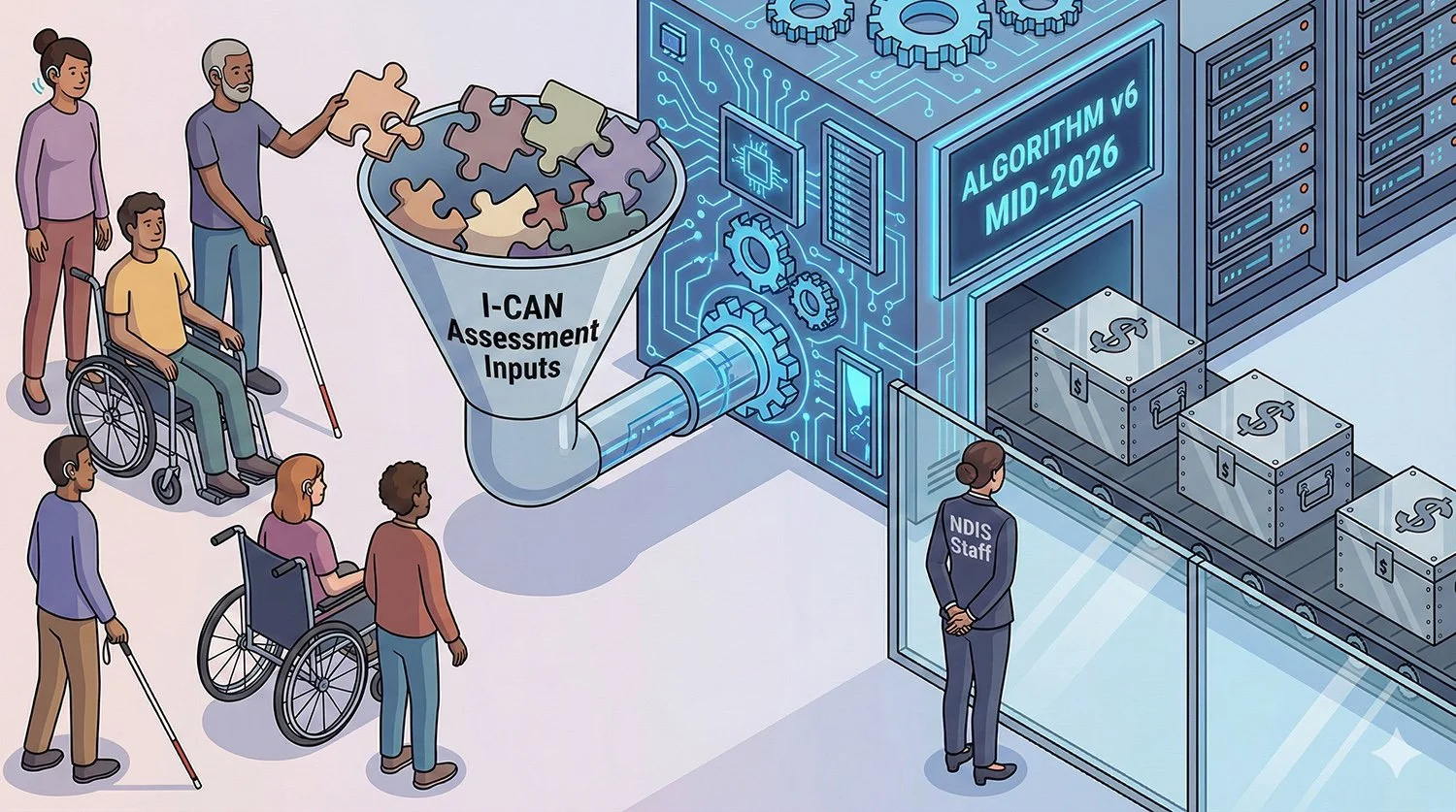

TGA position on “digital scribes”

The Therapeutic Goods Administration says digital scribes that only transcribe and translate conversations into written records without analysis or interpretation are not considered medical devices. If the system analyses or interprets conversations, for example by generating a diagnosis or treatment recommendation not explicitly stated by the clinician, the TGA says it is a medical device and must be included on the ARTG before supply in Australia.

The TGA also emphasises disclosure and consent: consumers should be told when a digital scribe is planned for their care, and health professionals are responsible for obtaining informed consent and verifying the accuracy of what ends up in the patient record.

ACSQHC clinical safety guidance

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s AI Clinical Use Guide (Version 1.0, August 2025) takes a clinician workflow view. It advises clinicians to critically assess the scope of use and evidence base, explicitly noting that AI development can outpace robust evidence in real clinical settings. It also flags that generative AI can produce non factual content (“hallucinations”) and warns about automation bias, urging clinicians to review outputs and remain responsible for final documentation and decisions.

The guide also points to practical governance, including monitoring performance over time, privacy considerations, and escalation pathways for serious patient consequences, including reporting adverse events for medical devices to the TGA.

A Reality Check on The Environmental Numbers

The University release includes environmental claims to underline that AI risks are not only clinical. Two updates are worth noting:

For global data centre electricity use, the IEA estimates data centres accounted for around 1.5% of global electricity consumption in 2024 (415 TWh). That is slightly higher than the “around 1 percent” figure quoted in the University release.

For Ireland, the “more than one fifth” claim aligns with official statistics. Ireland’s CSO reports data centres used 21% of total metered electricity consumption in 2023, and CSO reported 22% for 2024 (as covered by The Irish Times).

On model training emissions, instead of converting to flight equivalents, a peer reviewed estimate reports GPT 3 training energy consumption of 1,287 MWh and 552.1 tCO2e.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.