As Global AI Usage Hits 800M, Hong Kong Faces Access Restrictions

AI-generated Image (Credit: Jacky Lee)

As major US tech firms roll out new waves of artificial intelligence chatbot upgrades, users in Hong Kong remain largely excluded from direct access, highlighting the city’s increasingly awkward position between global AI innovation and tightening regulatory constraints.

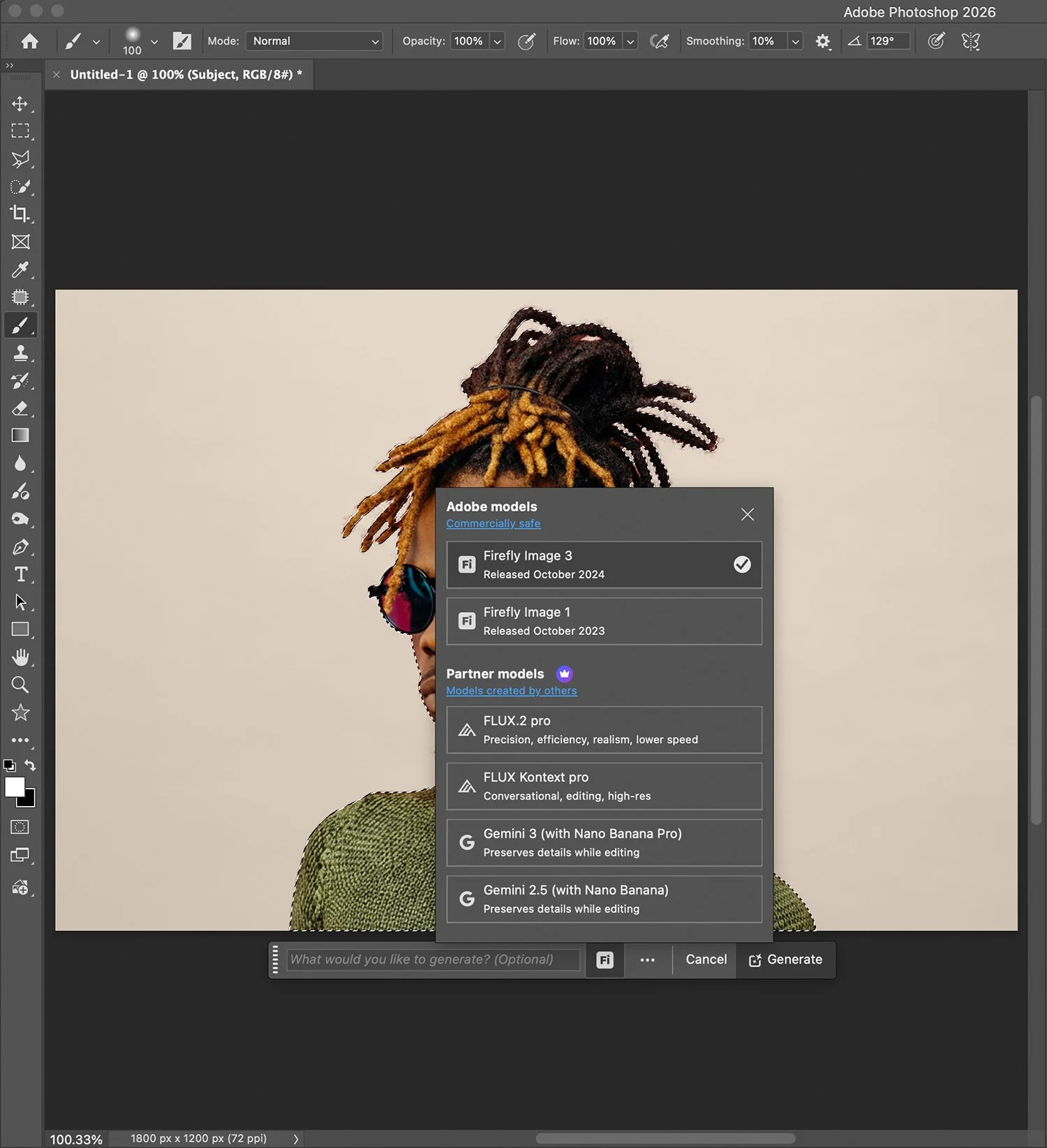

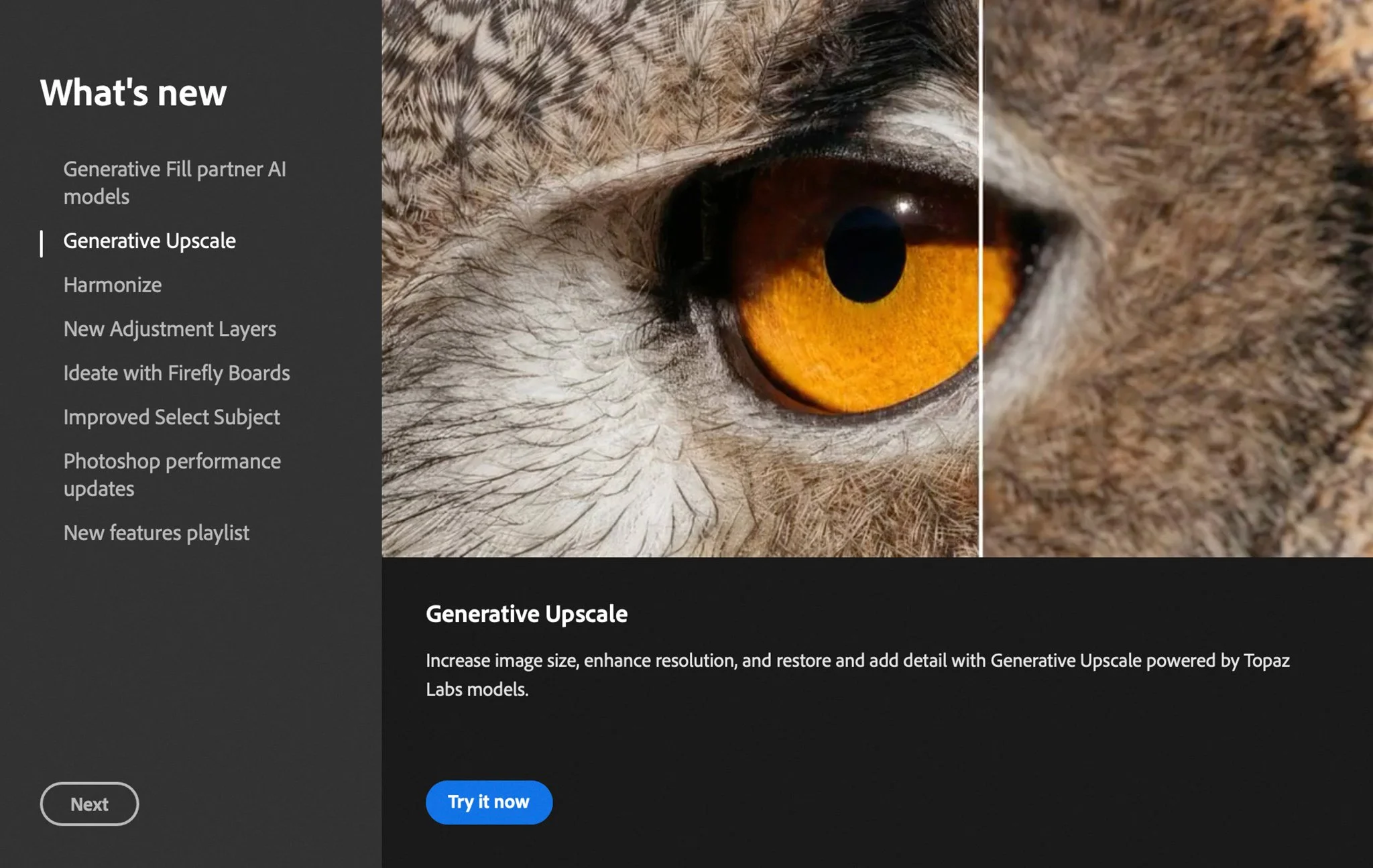

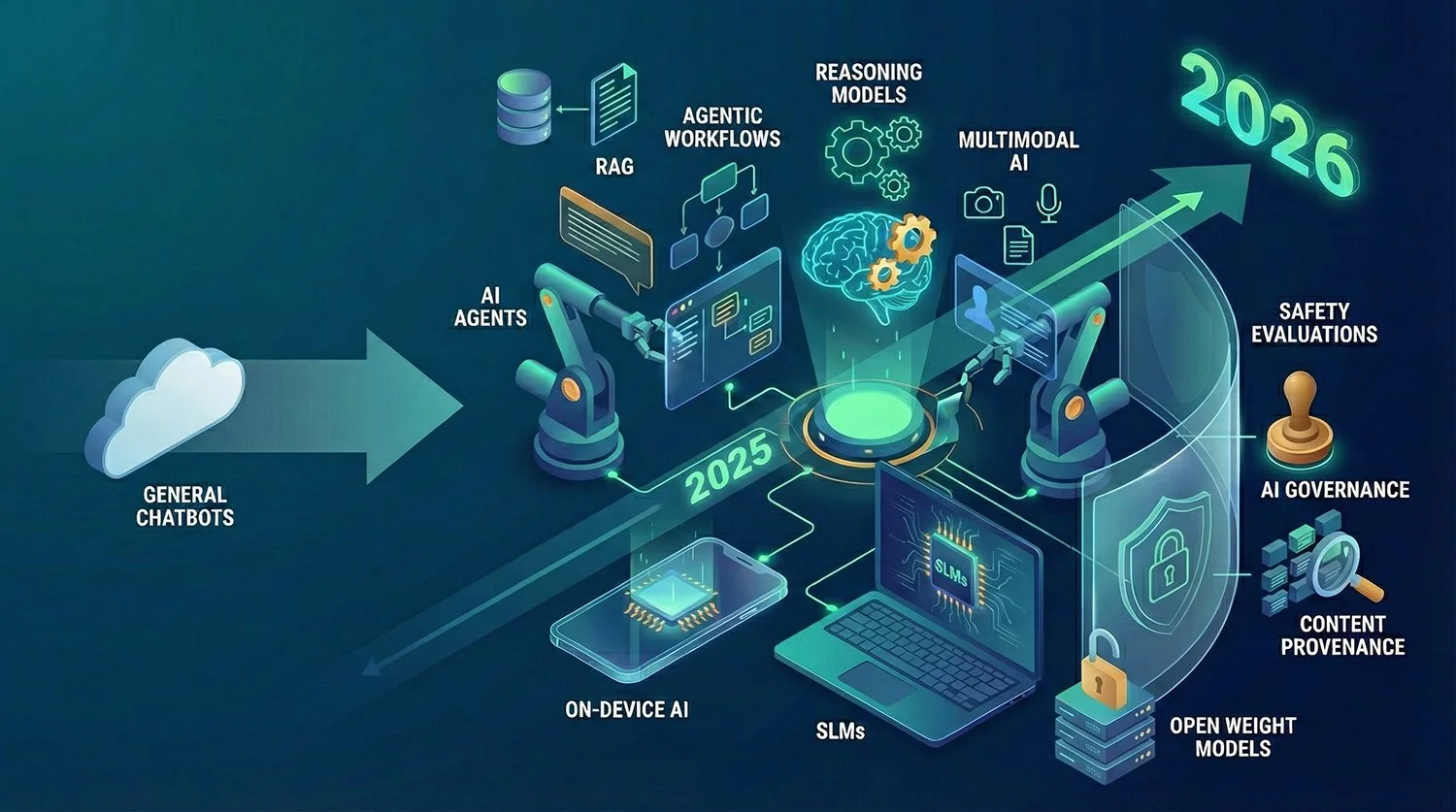

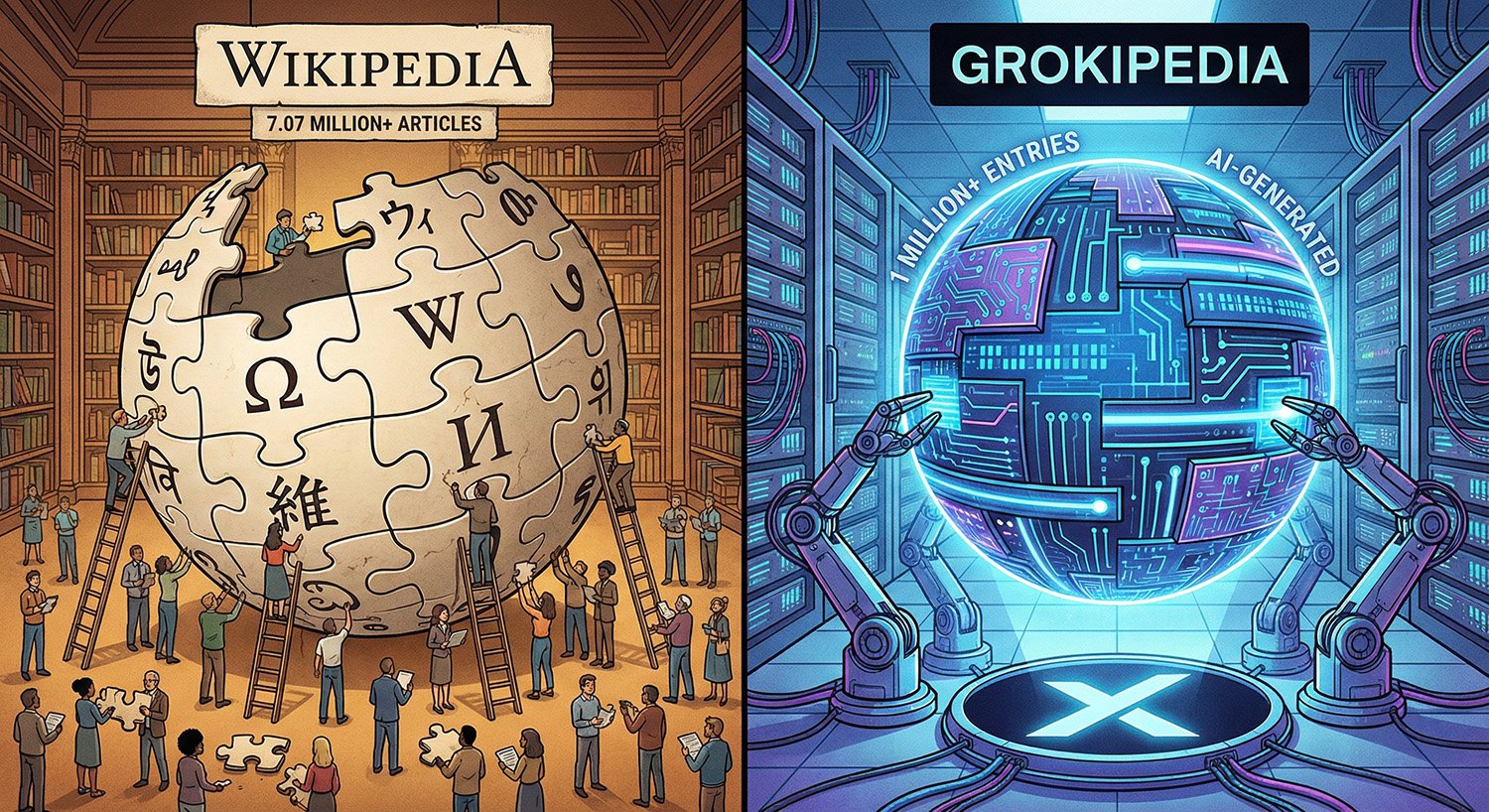

In 2025, OpenAI, Google and xAI all pushed fresh enhancements to their flagship models. OpenAI has continued to expand the capabilities of ChatGPT, including native image generation and editing based on its GPT-4o family and improved conversational voice features for paid tiers and enterprise products. Google announced Gemini 3 in November 2025 as its most advanced multimodal model so far, rolling it out across the Gemini app and Workspace integrations with stronger reasoning across text, images, audio and video. xAI, meanwhile, has iterated on its Grok system (including a Grok-4.1 release) with a focus on real-time information drawn from X’s social data streams.

These systems now serve very large user bases. OpenAI told Reuters in August 2024 that ChatGPT had more than 200 million weekly active users, rising to around 400 million by early 2025. In a later update, reported again by Reuters, the company said weekly active users had reached roughly 700 million by mid-2025. At OpenAI’s 2025 developer event, CEO Sam Altman went further, telling attendees that ChatGPT was being used by about 800 million people each week.

Yet in Hong Kong, once promoted as a bridge between mainland China and the global tech ecosystem, access to these tools is far from straightforward.

From “Gateway City” to Restricted Market

Hong Kong’s AI ambitions have been shaped by a series of policy moves over the past decade, including various “smart city” blueprints and its designation as an innovation hub within the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Universities, financial institutions and start-ups were among the early adopters of generative AI after ChatGPT’s launch in late 2022, and local professional bodies and think tanks quickly began publishing guidance on AI use in education, law and finance.

The operating environment shifted in 2024.

OpenAI access: Hong Kong is not listed among the supported regions on OpenAI’s official country and territory availability pages. In mid-2024, OpenAI began enforcing stricter blocking of attempts to access its services from “unsupported” locations. Hong Kong and Macau were widely reported as falling into this category alongside mainland China. The company has not issued a detailed public explanation specific to Hong Kong, but concerns over compliance, export controls and the city’s evolving national security framework are commonly cited by analysts.

Google Gemini: Google’s published list of countries where the Gemini web app is available does not include Hong Kong, even as the service has been expanded across North America, Europe and parts of Asia-Pacific. At the same time, Gemini models are available to enterprise customers through Google Workspace and Google Cloud, including in Hong Kong data regions. That means large organisations can use Gemini via commercial contracts even though ordinary Hong Kong consumers cannot simply sign into the Gemini web app with a local account.

xAI Grok: Grok is accessible through X (formerly Twitter) as a paid feature in markets where X Premium products are sold. xAI has not published a detailed country-by-country list comparable to OpenAI’s or Google’s, but Grok does not appear to be formally geoblocked for Hong Kong in the same way, and local users with X Premium subscriptions report being able to use the service.

Alongside these corporate decisions, Beijing’s Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region took effect in 2020, followed by the local Safeguarding National Security Ordinance in 2024. The resulting legal environment has increased perceived regulatory risk for foreign providers offering open-ended generative AI tools that could potentially generate politically sensitive content.

Compliance Risk, Export Controls and Legal Uncertainty

Several overlapping factors help explain why global AI firms are cautious about Hong Kong, even though it remains a separate customs territory and has its own common-law system.

Data protection and accountability frameworks: Hong Kong’s Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO), first enacted in 1996 and amended over time, sets rules for collection, use and cross-border transfer of personal data. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (PCPD) has published soft-law tools focused on AI, including the “Guidance on the Ethical Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence” and the “Model Personal Data Protection Framework for Artificial Intelligence”, both of which emphasise transparency, data minimisation and accountability for automated decisions.

These documents are influential but not standalone AI statutes. Taken together with the national security regime, they create a patchwork that overseas providers must interpret when considering how conversational models might handle user data and politically sensitive queries.

New government AI governance guidelines: In April 2025, the government’s Digital Policy Office (DPO) released the “Hong Kong Generative Artificial Intelligence Technical and Application Guideline”, a voluntary best-practice document developed with the Hong Kong Generative AI Research and Development Center (HKGAI). The guideline outlines risk-management, transparency and lifecycle-governance expectations for developers, service providers and users of generative AI.

Legal commentaries describe the guideline as an important reference point, but stress that it is advisory rather than a binding AI act. Businesses must still navigate PDPO, sector-specific rules and national security provisions, with no single consolidated AI law.

Financial-sector specific rules: The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) has issued guidance and circulars on the use of AI and big data in banking, followed by more specific remarks on generative AI that focus on governance, model risk management and potential bias in customer-facing applications. These requirements put additional pressure on banks and insurers that might otherwise experiment with off-the-shelf consumer chatbots.

Geopolitics and export controls: US export controls on advanced chips to mainland China have added a geopolitical layer to AI deployment decisions. While Hong Kong is legally separate in trade terms, many firms in the city are subsidiaries or partners of mainland-based groups, increasing scrutiny around potential “technology diversion”.

With tensions between Washington and Beijing continuing, US-based AI vendors can face heightened internal compliance scrutiny for any region perceived as a potential conduit for restricted technologies or high-risk data flows.

Against this backdrop, risk-averse companies have tended to exclude Hong Kong from consumer rollouts until the regulatory and political landscape feels more predictable.

Uneven Access and Productivity Gaps

The restrictions do not mean that generative AI is absent from Hong Kong, but they do shape who can use which tools and on what terms.

Large institutions vs smaller firms: Financial institutions and multinational corporations often gain access through enterprise channels – for example, by using Microsoft Copilot or Azure OpenAI Services, or by integrating Gemini models via Google Cloud under contracts signed in supported jurisdictions. These deployments come with legal review, data-hosting controls and bespoke compliance clauses.

Smaller firms, start-ups and individual professionals face more friction. Without direct access to ChatGPT or Gemini consumer products in Hong Kong, many rely on VPNs, third-party aggregators, or local models. This creates a divide between organisations that can afford structured enterprise access and those that cannot.

Education and individual upskilling: Universities and schools in Hong Kong have begun issuing their own guidelines on the acceptable use of generative AI for coursework and research. However, lecturers and students often report a patchwork of access: some institutions procure specific tools, while many individuals rely on personal accounts registered with overseas phone numbers or use intermediate services that expose only a fraction of the underlying models’ capabilities.

This can blunt the benefits of AI for everyday learning and language practice and complicate efforts to build AI literacy at scale.

Local providers and telecom-backed offerings: Telecommunications and IT firms have launched their own enterprise-grade chatbots powered by licensed large language models. For example, HKT offers an AI assistant product for businesses built on GPT-style models, with data hosting and integration tailored to local regulatory expectations.

These systems are typically positioned as privacy-conscious and on-shore, but they lack the brand recognition and broad ecosystem of tools like ChatGPT or Gemini.

The net effect is that Hong Kong businesses and residents can use AI, but often via indirect, more expensive, or less capable channels than counterparts in jurisdictions where consumer access to US chatbots is straightforward.

Mainland China, Regional Peers and Local Projects

Hong Kong’s position stands in contrast to both mainland China and nearby AI-savvy economies such as Singapore.

Mainland China: Mainland tech giants including Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent have deployed large language models such as Ernie Bot and Qianwen under licences from Chinese regulators. These tools operate behind content filters that restrict responses on politically sensitive topics, but they are integrated into office suites, search engines and developer platforms.

Cross-border use from Hong Kong is possible for some of these tools, but enterprise adoption is complicated by data-localisation rules and differences in privacy expectations.

Singapore and other regional hubs: Singapore’s government has actively promoted AI adoption, publishing national AI strategies and regulatory frameworks while allowing broad consumer access to global chatbots. Tech firms there commonly integrate ChatGPT, Gemini and other models directly into workflows, supported by subsidies and regulatory sandboxes.

Other regional centres such as Tokyo and Seoul have also moved quickly to incorporate generative AI into public services and corporate processes, again without the same level of access restrictions seen in Hong Kong.

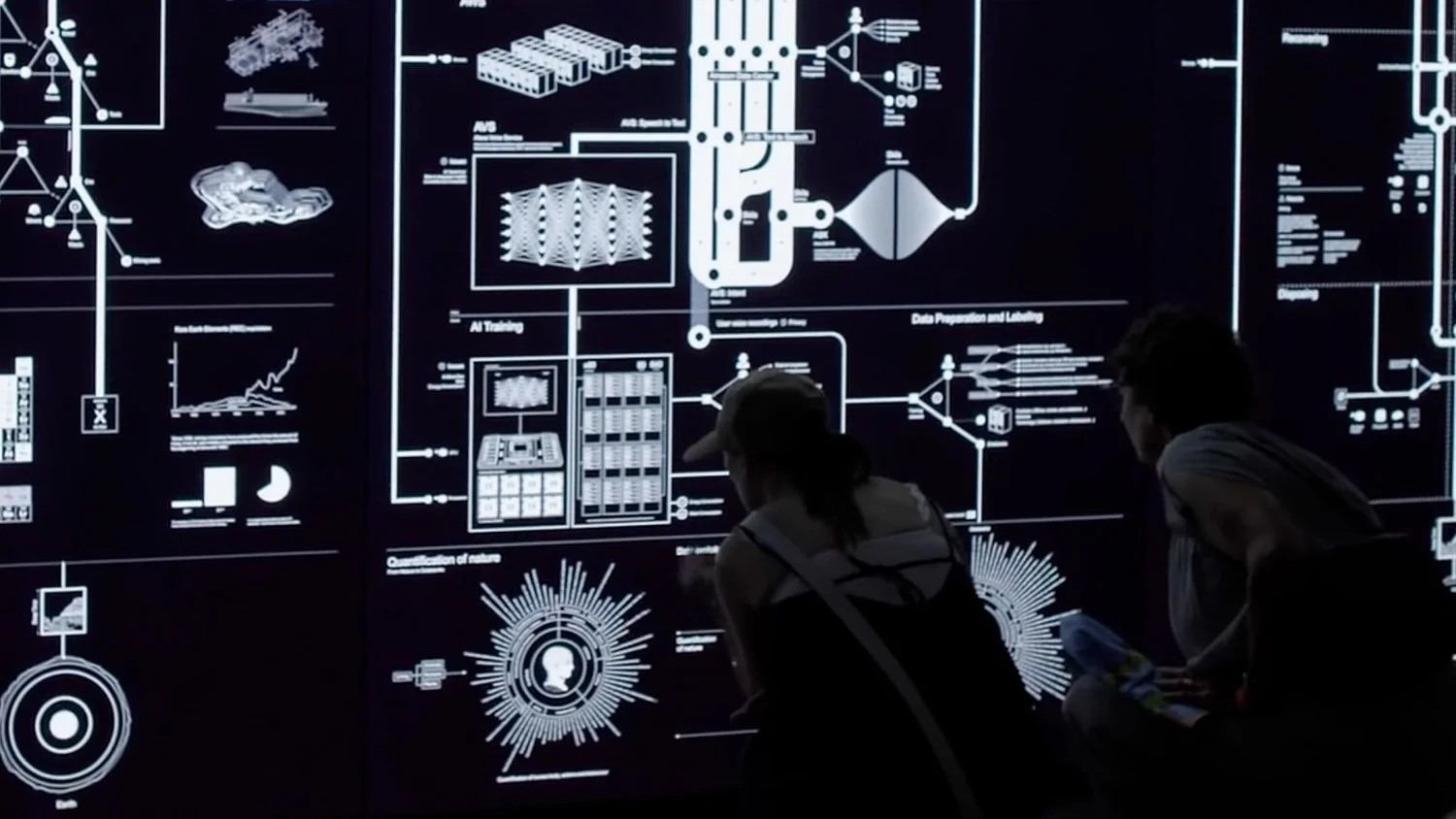

Hong Kong’s own AI infrastructure push: Hong Kong is not standing still. The Hong Kong Generative AI Research and Development Center (HKGAI), established under the InnoHK research clusters, released what it described as the city’s first home-grown large language model, HKGAI V1, in early 2025.

In March 2025, the Ng Teng Fong Charitable Foundation and Sino Group announced a HK$200 million donation to HKGAI to support, among other initiatives, development of “HKChat”, a multilingual chatbot service built on HKGAI V1 and aimed at Hong Kong residents. The donation was witnessed by the Financial Secretary and framed as part of a broader effort to boost local AI research and applications.

Legislative Council papers and policy speeches in 2025 also outline plans for a dedicated AI Research and Development Institute (AIRDI) to coordinate AI R&D, support industry adoption and link Hong Kong’s AI ecosystem more closely with the Greater Bay Area. Details of AIRDI’s structure and funding are still being debated.

These efforts underscore a strategic push towards “sovereign” AI capacity, even as global consumer tools remain harder to access.

Guidelines, Not Yet a Comprehensive AI Law

Regulators in Hong Kong have moved to clarify expectations around AI, but the regime remains fragmented compared with jurisdictions that have passed dedicated AI statutes. Key developments include:

Ethical AI frameworks (2021–2024): PCPD’s guidance documents on ethical AI development and AI accountability frameworks, which stress fairness, transparency and human oversight.

Sector-specific expectations from the HKMA and the Securities and Futures Commission on the use of algorithms in financial services.

2025 Generative AI guideline: The “Hong Kong Generative Artificial Intelligence Technical and Application Guideline”, released by the DPO in April 2025, provides detailed recommendations on governance, impact assessment, documentation, security and human-in-the-loop controls across the lifecycle of generative AI systems. Legal commentaries describe it as a voluntary, cross-sector reference point rather than a law with direct sanctions.

Responsible AI playbooks: Professional bodies such as the Hong Kong Chartered Governance Institute have published playbooks on responsible AI policy development, advising boards to implement internal governance structures, risk assessments and training.

Together, these materials sketch a regulatory direction: encourage adoption, impose duties through existing laws and sectoral guidelines, and provide soft-law guardrails for generative AI. But they do not yet answer the question that matters most to global providers: exactly how liability would be allocated if an open-ended chatbot deployed in Hong Kong generated content that regulators later deemed unlawful.

Local Models, Enterprise Channels and Conditional Re-Engagement

Looking ahead to 2026, several paths are visible for Hong Kong’s AI landscape.

Expansion of local and “sovereign” models: With HKGAI’s HKChat and similar projects, Hong Kong is experimenting with locally steered models that can incorporate Cantonese, traditional Chinese and local regulatory requirements more directly. Government speeches in 2025 indicate that these models may be deployed in more public-service workflows, from document summarisation to internal knowledge search.

Greater use of enterprise gateways to global models: Microsoft, Google and other cloud providers are likely to remain the main legal channel through which large Hong Kong organisations use models such as GPT-4o and Gemini 3. This approach allows contracts to be framed under clearly specified jurisdictions and data-processing terms, while minimising provider exposure to consumer-facing national security or speech disputes.

Potential for more unified AI regulation: Legal commentators and policy trackers have suggested that, over time, Hong Kong may move towards a more unified AI framework that consolidates PDPO, national security requirements and sectoral guidance into a clearer regime. The 2025 generative AI guideline and the proposed AIRDI are seen as steps in that direction rather than endpoints.

Consumer access remains uncertain: Whether OpenAI, Google and others will restore full consumer access to their chatbots in Hong Kong is unclear. Given the rapid growth of user bases elsewhere and ongoing geopolitical tensions, Hong Kong is a relatively small but symbolically complex market. Firms may wait for more regulatory clarity or rely on enterprise offerings as their primary presence.

For now, Hong Kong sits in a distinctive position: highly ambitious about AI, equipped with strong research institutions and new funding for local models, but constrained by a mix of geopolitical risk, national security law and cautious corporate risk management.

Residents and companies can – and do – use generative AI. But they often do so through indirect channels, local alternatives or enterprise gateways, rather than the consumer-grade ChatGPT or Gemini apps that have become everyday tools in many other parts of the world. How long that gap persists will depend as much on international politics and corporate risk appetite as on Hong Kong’s own policy choices.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.